insight

When the impacts of COVID-19 were first felt in Australia in March, patients and clinicians flocked to use virtual care, mainly through telehealth. Given the imperative for social distancing and the uncertain effects of the virus, neither patients nor clinicians wanted to put each other at risk.

The funding system soon followed, with the Medicare Benefits Schedule introducing telehealth billing items. (By May about one-third of the 16 million consultations were for telehealth.)

Now patients and their families have experienced the benefits of virtual health, they are unlikely to go back. Several months on, many specialists are caring for patients they have only met virtually, showing it can be done successfully. There is every indication that virtual care is here to stay.

Keen to understand more about virtual care, in late July Nous hosted a virtual roundtable to discuss the issue. Our panellists, Adjunct Associate Professor Cheryl McCullagh and Professor Rod McClure, explained their experiences ahead of a broader discussion with about 20 people across the Australian health care sector.

I am pleased to share some insights from the event.

Virtual care brings benefits to all stakeholders

When we talk about virtual care, we are talking about a suite of services where the interaction between clinicians and the patient is not in person. This can include everything from video consultations with doctors, real-time sharing of information, remote monitoring of patients’ health and use of analytics to support diagnoses.

There are several major drivers of virtual care. Firstly, system administrators want to reduce hospitalisation rates, unnecessary outpatient events, length of stay and in-hospital care costs. Meanwhile patients and their families want to reduce disruption to their lives and have choice about where and how treatment occurs. And this year COVID-19 has challenged the idea that in-person care is the default option.

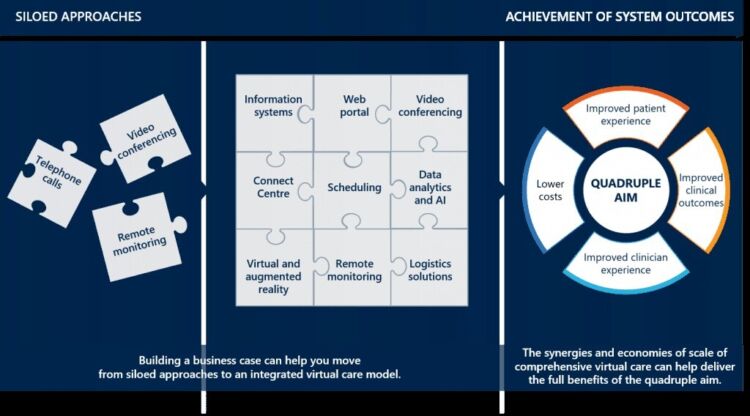

Currently, most uptake of virtual care is well-intentioned but piecemeal, with models offering a single service and not integrated into each other or the broader health system.

The full potential of virtual care can only be unlocked when health leaders embrace a transformative approach to implementation. Benefits include:

- economies of scale for services and greater access, equity and choice for patients in the delivery of care and treatment

- coordinating different virtual care elements to create an integrated service model

- greater efficiency and networking among different parts of the health system, including primary and secondary care, research, technology providers and education

- solutions to long-standing health system issues, such as shortages of resources in regional areas leading to reduced access to services and poorer health outcomes

Lessons emerge from those who are doing it

As CEO of the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network, Cheryl McCullagh has sought to create Australia’s first virtual kids’ hospital network.

Cheryl told the roundtable that while virtual care may be front of mind today, medical experts have for decades reached out to their patients using telecommunications.

Since the disruption of COVID-19, many patients and practitioners have enthusiastically adopted virtual care, with the number of telehealth consultations up significantly. Nous’ work with the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network found that 30 per cent of outpatient consultations could be done via telehealth. “Choice is actually what families want and clinicians are willing to work with different mediums,” Cheryl explained.

Typically, families who come to a hospital will have three connected electronic devices at home, such as a smartphone or computer, with just 1 per cent having no devices.

“We know that families who can communicate with their clinicians when they feel like it via a secure app feel safer at home,” Cheryl said. “This is really important work to provide a better care experience for patients and families and also provides a safer work environment to deliver care for clinicians.”

Rather than just replacing in-person consultations, virtual care can substantially improve patient outcomes. Creating a detailed electronic record generates an opportunity to turn data into service improvement and clinical actions.

Ultimately, benefits can include improved clinical care, health system efficiency, health outcomes, patient experience and access to clinical trials, alongside decreased family disruption.

Also sharing his experience was Rod McClure, who as Dean of the Faculty of Medicine and Health at the University of New England has created the region’s first virtual health network.

Rod told the roundtable that virtual care was delivering benefits to regional, remote and rural communities, where the health system was at risk of collapse in some cases. He noted that efforts to fill 35 general practitioner training positions in the New England region in the past year had yielded just eight placements.

A virtual health service can provide a solution, he said, offering a network of activities to deliver an intervention. “We’ve got to somehow overcome the fragmentation of what we have here to create a strengthening of existing systems using the digitally enabled technologies we have access to,” he said. Done right, virtual care can enhance the exchange of knowledge between students, patients and clinicians.

Nous was pleased to partner with both the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network and the New England Virtual Health Network to support their development.

Virtual care has impacts on the system, services and clinicians

Thinking about virtual care, it is useful to think about the impacts at three levels: the system, the service and the clinician (and therefore the patient).

System

To be effective across a system, virtual care needs to be centrally orchestrated. The traditional clinical governance models, built around clinicians seeing patients, need to be adapted to the virtual environment.

Virtual care requires a robust quality and safety model to ensure best governance, as well as a comprehensive and coordinated approach that ensures the different parts of virtual care work together. A good virtual care model can improve governance across primary health networks and local health and hospital services.

While the new telehealth items on the Medicare Benefits Schedule have been well received, pricing authorities need to consider the long-term impacts on funding models and embed these item numbers so they are available after COVID-19. Clinicians we have spoken to are hesitant to change anything until there is action to make this funding available.

An effective model for virtual care requires careful measuring of outcomes. From the outset, the model should feature an evaluation committee tasked with robust measurement. This can be embedded at both a system level and a service level. After identifying the outcomes the model is intended to deliver, measurement methodologies should range from simple evaluation methods through to randomised controlled trials.

Service

Primary health care has a major role to play in the rollout of virtual care. Primary care services need to oversee an integrated care model, which requires ensuring tasks get done rather than getting caught in disagreements over demarcation.

To be done effectively, integrated care may require building a ‘command centre’ and improving sometimes-clunky scheduling tools. Integrated care also requires moving beyond episodic funding, which does not allow for the necessary pooling of funds.

Virtual care can be particularly useful for reaching patients at risk of falling through the cracks in the system. Technology can enable clinicians to reach patients who might shun in-person appointments, for reasons of geography, finances or personal circumstances.

Many rural areas are grappling with the balance between delivering primary care and acute services. This can in part be achieved by creating a network of service providers – generalists and specialists – connected and working together using virtual care technologies.

When patients are dispersed, it significantly reshapes the triage and assessment process. A nurse, or team of nurses, can undertake remote monitoring, typically sitting in front of a screen to monitor multiple patients. More and more this is being supplemented with analytics programs or artificial intelligence (AI) systems to flag risks and alerts and to prioritise virtual ward rounds. In addition, patients are becoming empowered to know more about their own health and can manage more by themselves.

While modest efforts in virtual care can be done using existing resources, soon most health care providers recognise the need for additional funding. This necessitates a business case that shows the benefits, not just in financial terms but also in health and social terms. It may be that launching new systems involves retiring old systems rather than running them in parallel.

Clinician

Effective change management requires strong leadership and a narrative to build support and enthusiasm among clinicians. Support from patients and their families can help build the narrative and win over clinicians. This can be helpful in maintaining momentum even if there are occasional technical bugs.

It is useful to start with the early adopters and then encourage take-up among more reluctant cohorts. It is important to keep nudging clinicians further along the curve – say, shifting from telephone consultations to those done by video. In May 2020, just 9 per cent of telehealth consultations were via video, with the remainder being via phone.

Ultimately the explanation of the desired state needs to be vague enough for everyone to see how they can fit into it, while also showing practical outcomes and building excitement.

The next step is implementation

Already the technology to remotely support population and individual health exists. Now health services need to invest in physical infrastructure that embeds technology into hospitals and the broader health care system, changing the way care is delivered.

And when we come out the other side of COVID-19, we need to make sure that we do not snap back to old ways of working and instead embed virtual care models alongside traditional care models.

At Nous we have worked to support health services, including the two featured in our roundtable, to develop, rationalise and implement bold ideas for virtual care.

We have found that success comes when skills from the domains of health care, change management, organisational strategy and technology are combined to develop solutions that endure.

Now that all parts of the health system have experienced the impact of virtual care, it is here to stay. The questions are what form it will take and how it can be used most effectively.

We thank Cheryl McCullagh, Rod McClure and everyone involved in our roundtable.

Get in touch to see how we can work together to put virtual care to work in your organisation.

Prepared with input from Hilary Bush, Ian Sheldrake and Steve Teulan.

Connect with Raj Verma on LinkedIn.