insight

Across Australia, communities and justice authorities are feeling the strain of a growing number of people having encounters with the justice system. Jails are at capacity, court backlogs are accumulating and police services are being tested.

For offenders and their families, these encounters can cause frustration and make it harder for them to move on with their lives, increasing the risk of recidivism and intergenerational disadvantage. And for justice officials, the burden can sap resources and lead to low morale and poor performance as the system comes to resemble a revolving door.

But what if there was another way? What if we could divert people away from the justice system early, so they can get the support they need to lead lives with less risk of entanglement in courts and prisons?

It is not new for individual justice services to consider ways to reduce demand, but it is rare for those overseeing a whole system to think about what they can do to alter the life course of individuals encountering the police, the courts and prisons.

From our experience at Nous Group, it is clear that interconnected help across government agencies (including in justice, health, education and social support) and community organisations is critical to reducing the number of people on the path to corrections.

‘Exit ramps’ and ‘toll booths’ play vital roles

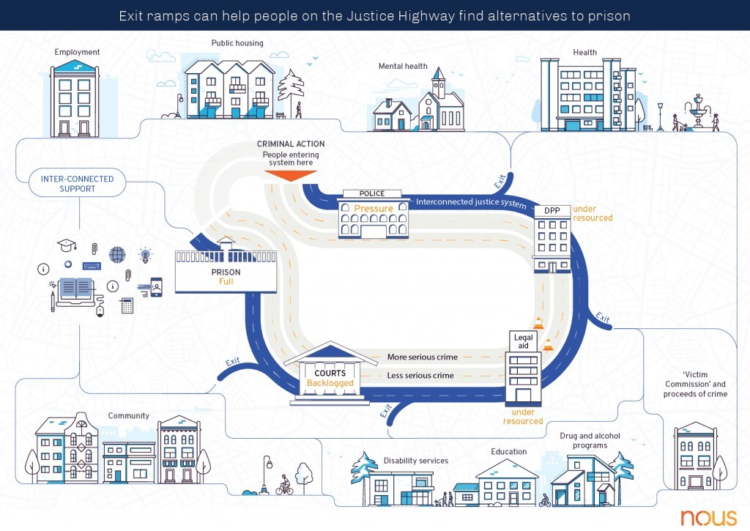

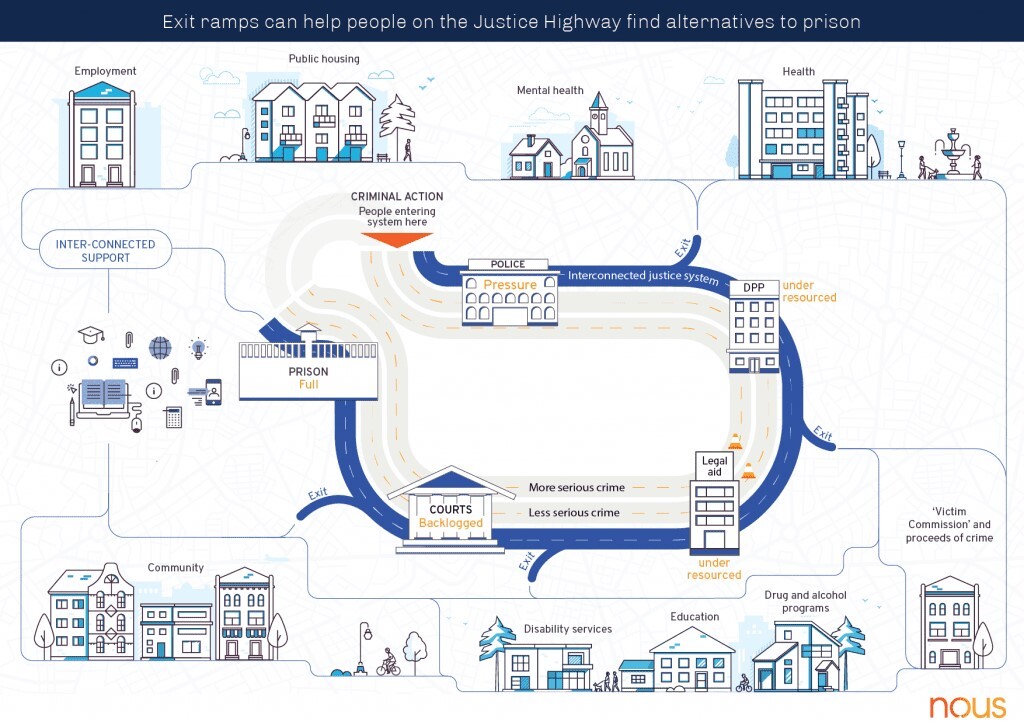

It is helpful to think of the justice system as a multi-lane highway, along which people encountering the law are travelling. People enter the highway when they commit a criminal act, and if they stay on will end up in prison. Along the way are several exit ramps, but getting to them is not always easy. Unless a traveller is interrupted at a toll booth, those exit ramps may not even be visible.

Exit ramps on the highway are support services, including accommodation providers, mental health and disability services, and drug and alcohol programs. To be reached, they must be seen and be accessible. And once a person leaves a service they need adequate help – such as to engage in education and employment – otherwise it may prove easier for them to loop back onto the highway than to take the off-road.

As for toll booths, they can include Legal Aid, the Director of Public Prosecutions and the courts system itself. At these points, thoughtful sentencing focused on rehabilitation can funnel people towards the exit ramps.

Right now, in many jurisdictions a lack of communication between justice agencies and community organisations that offer support means many people are not assisted to exit the highway. Therefore, many people end up in prison when that outcome could have been avoided. Leaders of the justice system can create opportunities for people to access exit ramps and reach better destinations.

Prisons are expensive and have high rates of recidivism

There is little evidence that prisons are effective in correcting criminal behaviour. Research from the Institute of Public Affairs found that 45 per cent of prisoners released during 2013-14 returned to prison within two years. People who went through community-based corrections had a much lower rate of recidivism (though this rate remains high, so there is clearly room for improvement).

Beyond the risk of recidivism, there is a massive impact on victims of crime, offenders and their families, and the sustainability of justice systems.

Australian prisons are expensive and overcrowded. It costs $110,000 a year to imprison a person, making Australian prisons the world’s fourth most expensive per prisoner. The number of prisoners stood at 42,974 in 2018, up 40 per cent over the previous five years.

Community-based corrections is considerably cheaper than prison, yet is underutilised. In 2017/18, Australian jurisdictions spent $3.4 billion on prisons, and just $600 million on community corrections. Consider the benefits if community corrections were an exit ramp on our Justice Highway.

Better outcomes are possible at each step

Prisons’ high rate of recidivism and cost show that more needs to be done to achieve early intervention. There are several steps justice systems can take to support more people to avoid prison:

- Easier access to support before incarceration. By creating more toll booth interruptions along the journey, there can be more opportunities to divert people towards support programs. Most people have multiple contacts with the criminal justice system before being incarcerated, and we know that offending behaviour is often linked to other social and health problems.

- More early intervention. Better funding for a wider range of interventions can mean that people in the judicial system are more likely to find an exit ramp alternative that meets their needs and suits their life circumstances. Multiple contacts, and an understanding of other social and health problems, offer points of intervention.

- Improved support in prisons. Prisons provide an opportunity to engage people in education, vocational training and health services, but Australian prisons fall often fail to realise the potential. Where presently prisons increase the chances of reoffending, it would be beneficial to equip incarcerated people with skills to cope after release.

- Better support for released prisoners. Upon release from prison many people struggle to find housing and employment, increasing their risk of recidivism. Greater provision of stable accommodation, including transition houses, and labour market support can help people reintegrate into community life. This can reduce the chances of former prisoners disengaging from support services, or reoffending in order to get the small comforts that prison life offered them.

- Coordination and information-sharing. By collaborating more closely, government agencies can help people successfully transition out of an institutionalised environment. Many former prisoners have efforts to avoid recidivism hampered by gaps in service agencies, such as the difficulty of accessing identity documents and establishing a bank account after release.

Some jurisdictions are reporting pleasing results through these sorts of initiatives. The Queensland Government’s Youth Justice Strategy involves Transition to Success (T2S), an alternative education and occupational training program for young people at risk or in the youth justice system. An evaluation found that of the young people who had a history of offending, 57 per cent who completed the program did not reoffend within six months; by comparison only 41 per cent who did not participate in T2S but were otherwise equal did not reoffend. This difference in offending meant that for every dollar spent, there was $2.50 in avoided costs of crime custody and supervision.

Several practical steps can set early interventions on a path to success

If we accept the benefits of diversion from prison, and we accept the steps to get there, the final challenge is putting in place the policy settings to enact those diversions.

It is critical that justice leaders come together each year to plan these pathways. Practical measures that must be discussed include pooling budgets, identifying the potholes in the way of the exit ramps, and establishing the best ways to divert people off the highway.

It can be helpful to build an evidence base to achieve the desired policy settings. This can involve evaluating current approaches to crime prevention, considering the approaches in other jurisdictions and piloting new programs to assess their impact.

The community needs to be brought along for the transition, through regular consultation and feeding back of information. Groups that provide services need to know how they will operate in the new environment, and victim and prisoner advocacy groups need to be kept involved.

Once a system-wide consensus is reached, resources and priorities across the justice system need to be aligned. While additional resources would always be welcome, redeploying existing resources to meet new objectives means that some parts of the system may get less and other parts will get more. South Australia Police has had particular success with its Organisational Reform District Policing Model, which creates flexible work groups supported by centralised functions that reduce the demand for police services, so it can focus on protecting victims of crime.

All parts of the justice system then need to collaborate and share information. While some of this can occur through more informal arrangements, in order to routinise these practices it will probably involve formal agreements between different parts of the system. Technology can help to achieve a smooth flow of information that protects people’s privacy. It is useful to observe the Northern Territory, where a Cross-Agency Working Group to reduce domestic, family and sexual violence has been tasked with driving collaboration, engagement, information sharing and problem resolution between Territory Families (a government agency) and partner organisations.

Players of the classic board game Monopoly are familiar with the square featuring a stern police officer with an outstretched finger telling them to go to jail. For some people this direct path to prison matches their experience in the real world.

When on the Justice Highway, let us ensure the signage makes clear how people can get down the ramps to support and services, rather than reaching prison.

Get in touch to discuss how we can help your organisation improve the justice system.