Idea In Brief

Reduced effectiveness

We know housing and mental health are interlinked: housing (and other social determinants of health) contributes to 80 per cent of health outcomes, while housing instability can trigger and exacerbate poor mental health.

Greater change

Housing and mental health services remain overstretched and siloed. There are instances of good practice, where frontline services and policymakers across health and housing are making inroads. But greater change is needed across the system.

Big and small steps

Changes include: Ensure new housing investments break down siloes; Centre lived experience; Use data to drive decisions; Commission services with care; Work as a team; Embrace innovation; and Use incentives and accountabilities.

Across Australia, there are dual crises in our housing and mental health systems.

We know housing and mental health are interlinked: housing (and other social determinants of health) contributes to 80 per cent of health outcomes, while housing instability can trigger and exacerbate poor mental health.

Policymakers have long identified this relationship, but few have been able to solve the problem.

In this article we seek to explore the problem and identify pragmatic responses. This is informed by conversations with staff from WentWest Primary Health Network and Youth Off the Streets.

We pay our respects to the traditional owners of the lands throughout Australia. We also acknowledge people with lived experiences of mental ill health, homelessness and housing insecurity. Experiences and perspectives of housing and mental health are different across different people. It is important to consider the holistic social and emotional wellbeing of people, their families and their communities.

People need safe and stable housing to focus on their mental health

Experiences of unstable housing and homelessness limit the effectiveness of mental health supports. Stepped-care and recovery-oriented models seek to empower people as experts in their mental health care, building hope and providing the right care at the right time. This is difficult to achieve without safe and secure housing.

Across Australia, major shortages of housing supply are causing severe challenges for many people, particularly those experiencing mental ill health. While governments are investing in housing – nationally and in several states – it will take a long time to realise the benefits.

Around half of people seeking homelessness support are not getting their needs met. Systemic stigma and discrimination and high costs in the private rental market are significant barriers for people with mental ill health. This September the national vacancy rate hit 1.1 per cent, a record low.

These shortages are mirrored in mental health services. Severe shortages in community mental health services mean many people experiencing housing instability cannot access the mental health supports they need. The problem is particularly apparent for the ‘missing middle’: those with moderate to severe mental illness who are too unwell for primary care but not unwell enough for acute services.

Overstretched housing services are being forced to provide stop-gap measures to support people with mental ill health without proper support or training, or to turn people away because they lack the capacity to safely support peoples’ mental health needs.

There is also a significant community cost. People experiencing mental ill health and homelessness are likely to have longer stays in acute mental health units, present more to emergency departments, and have more contact with the justice system compared with those who have access to stable housing.

A recent 13-year study in Sydney examined hospitalisations among people who attended homeless hostel clinics and found the median cost of hospital treatment was $81,481 per person. This amounted to a total cost of $548.2 million for 27,466 admissions over that period.

We need to take steps towards system change

While the challenges are well known, housing and mental health services remain overstretched and siloed. There are instances of good practice, where frontline services and policymakers across health and housing are making inroads. But greater change is needed across the system.

This can be achieved. There are big and small steps we can take.

1. Ensure new housing investments break down siloes

For the first time in decades there is significant momentum to address the housing crisis. With billions of dollars being invested, it is vital that this money is spent well and supports those that need it most.

There is wide recognition that Housing First models – where people are provided with long-term housing and wraparound supports – work best.

Pockets of good practice are emerging, including Victoria’s investment in 2,000 homes for people living with mental illness as part of the Big Housing Build. Housing First models are challenging to achieve at scale and must be adapted to local contexts through multiple levers.

Nous has worked with governments to activate these levers. For example, we worked with a state government housing agency to help it make the case for prioritising social housing. This involved population-based demand modelling and an options paper on managing demand. This work showed the need for different parts of government and the private sector to work collaboratively.

2. Centre lived experience

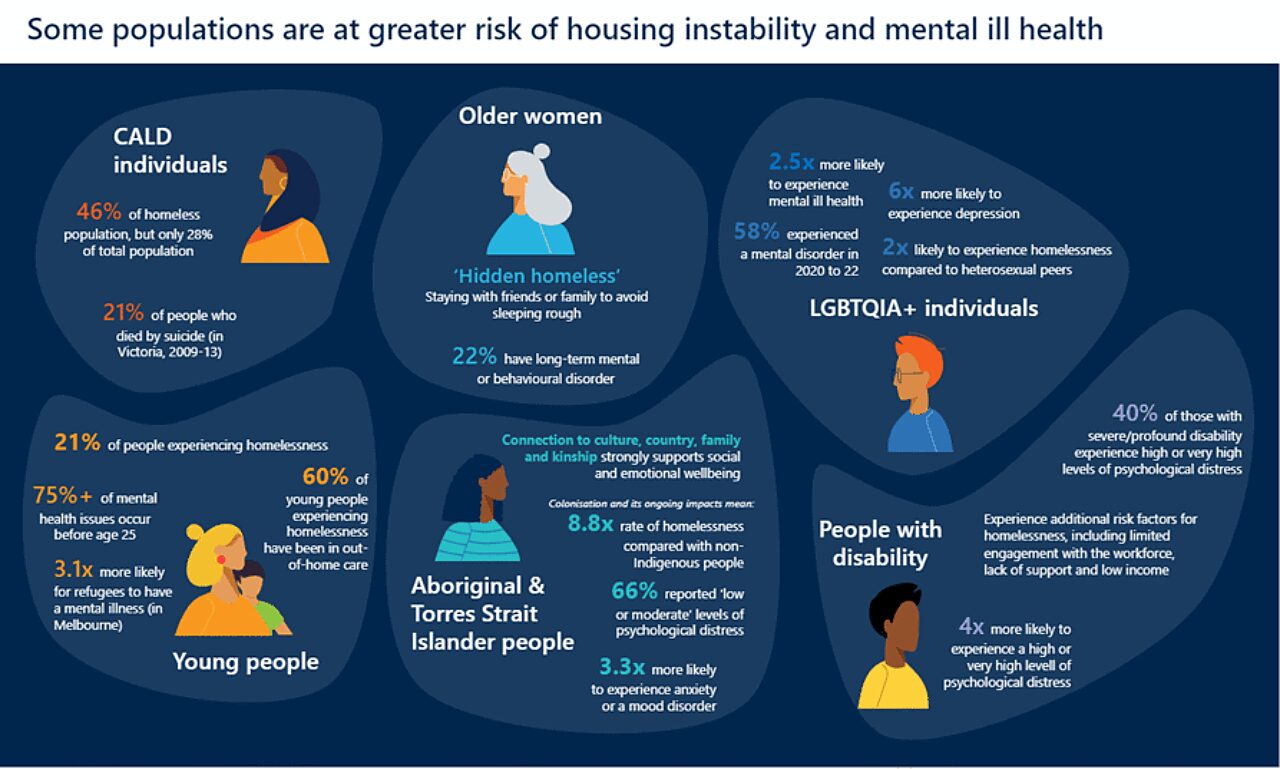

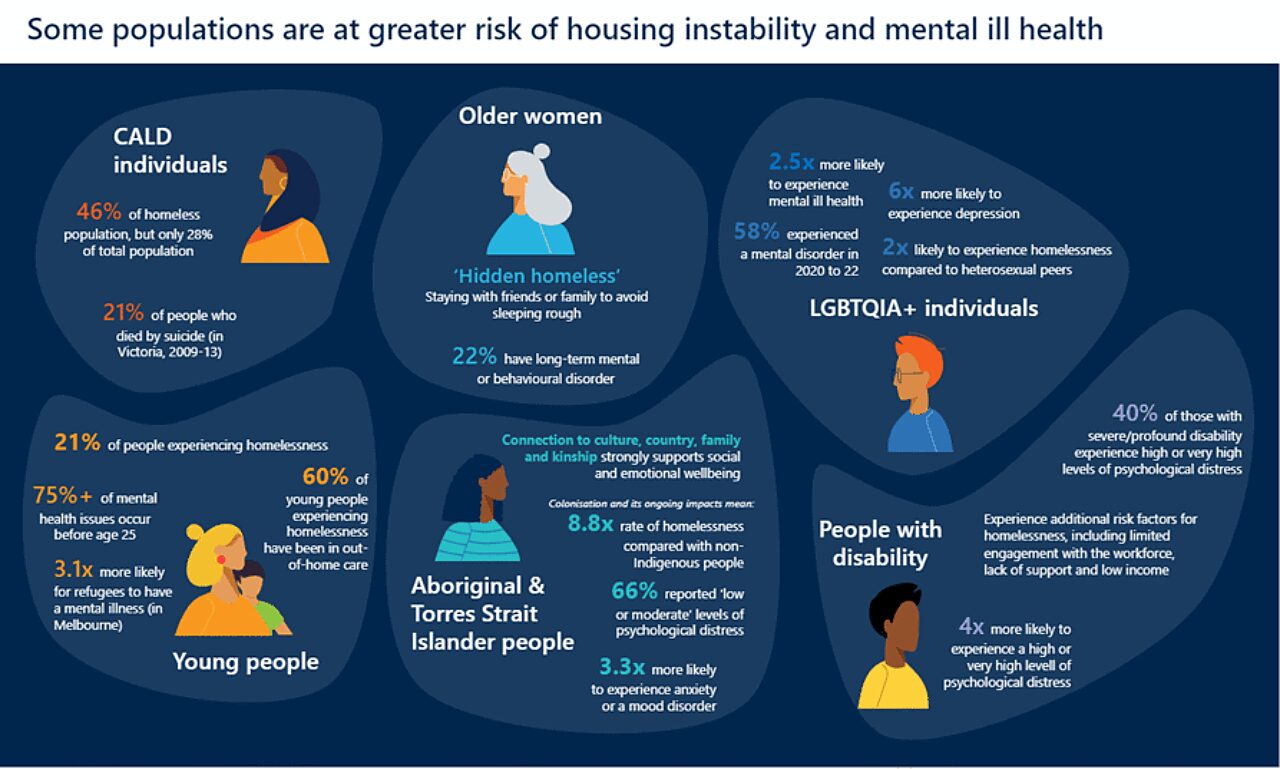

Empowering people with lived experience leads to better outcomes, research shows. Human-centred design ensures that solutions are based on the actual needs and experiences of the people impacted. Supports should be tailored for diverse populations, including First Nations, youth, and CALD (culturally and linguistically diverse) people.

In one project, Nous took a human-centred design approach to improve access to alcohol and other drug (AOD) information and support. This was undertaken in partnership with an Aboriginal peak body, who provided Aboriginal governance over this work and guided our engagement with Aboriginal peoples and communities. The work has involved consulting people, families and communities with lived experience of the impacts of AOD. This has helped us to identify common challenges and barriers to people accessing information and support, and opportunities to address these barriers. We are working with service and system stakeholders to identify the requirements for implementing these solutions.

3. Use data to drive decisions

Better data and data-sharing will allow people on the frontline and in the boardroom to focus effort where it is needed most. Current data is patchy and incomplete, meaning we lack an accurate picture of how many people are impacted by housing instability and mental ill health.

Service providers and funders should seek to improve data collection, analysis and reporting. This includes linking data to understand people’s experiences across the system and highlighting where additional data is required. Where gaps are identified, codesign approaches with people with lived experience and priority populations to ensure data accurately represents people accessing mental health and housing services. For example, mental health and homelessness can mean different things to CALD populations, while Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are more likely to live in between houses with extended family networks and consider their mental health as part of their broader social and emotional wellbeing.

Some mental health services have found a gulf between the number of people reporting homelessness and the number of people actually experiencing homelessness. For individuals, this means basic needs are undetected and so not provided. For the system, under-reporting limits our ability to plan and commission services that respond to actual local and community needs.

By improving our data collection mechanisms and data quality, we can plan and commission mental health and housing services more effectively. For example, more mental health services are seeking funding for brokerage services to support people experiencing housing instability. Data-informed planning would allow funders to anticipate this need and build it into funding contracts.

Showing the power of data, Nous supported Western Australia’s Ministerial Taskforce into Public Mental Health Services for Infants, Children and Adolescents, which sought to ensure adequate and equal service provision for children and young people through data modelling.

4. Commission services with care

The proportion of social housing available in Australia sits well below other developed countries. Australia’s rate – 3.8 per cent – compares unfavourably with the European Union median (6.0 per cent) and the United Kingdom (20.3 per cent), according to 2021 data. When looking at demand, approximately 6.1 per cent of all Australian households were living in, or had requested to live in, social housing. This represents an unmet demand of 213,847 households.

Funders and services should plan and commission to respond to local needs. Joint planning for mental health and housing services recognises the influence each sector has on the other and ensures there are adequate services for people with co-occurring needs. Co-commissioning among funders enhances visibility of available services.

Existing mental health services should be expanded to meet the needs of people in the ‘missing middle’ and have a greater focus on housing and other social determinants. Without this support, the complexities of presentations for this group will worsen, which can lead to mental health and housing crisis.

Funders should provide long-term funding contracts to commissioned services to support long-term planning and a genuine commitment to meet the needs of people with mental health and housing needs. Longer-term funding provides the stability for services to develop community partnerships, plan for the long term, and trial and evaluate innovative solutions.

Nous worked with the Queensland Government to develop commissioning processes for bail support programs that are led by ACCO (Aboriginal community-controlled organisations). These programs are long term and balance whole-of state outcomes with flexibility for local services to deliver culturally appropriate supports.

5. Work as a team

Frontline workers show innovation and creativity to meet the needs of people with limited resources, but they are overstretched and need better support to respond to mental health and housing needs. Australia’s system of support is siloed, with areas of specialisation to meet specific needs. Frontline workers need support to recognise and respond, to be creative, to solve problems and to support people to connect to other services – and in all of this, to collaborate with people from other services.

Services should develop a culture that encourages and enables service providers to collaborate with each other and respond to holistic needs. This includes training for frontline workers to recognise and respond to social determinants.

Funders should facilitate collaboration between sectors by providing networking opportunities and funding joint initiatives. Commissioning bodies have visibility of services delivering mental health and housing support, and of local needs.

Funders should explore collaboration strategies. Colocation of mental health and housing services would improve coordination of care and increase the knowledge, skills and confidence of frontline workers to recognise and respond to presentations in areas outside of their expertise, research shows. Multidisciplinary teams can improve identification of and response to the mental health and housing needs of people accessing services, further research shows.

6. Embrace innovation

Funders should build on the work of community-based service providers.

For example, the Kids and Early Years (KEYS) Network is an interagency initiative in Western Sydney that supports collaborative and child- and family-centred approaches between health, social and education providers. It is led by WentWest. The program targets families with children aged under 5 and enables multiagency wraparound care, continuity of care, and service navigation support. KEYS works with families’ existing service providers to find solutions to housing and food instability, domestic and family violence, school attendance, and neurological and school readiness assessments.

Another example is NSW’s Youth Off the Streets, which is delivered by dedicated staff to support young people experiencing homelessness with wraparound supports, including crisis accommodation, counselling, and skills to support independent living and community connection.

In Western Australia, Nous worked with government to develop a service model to respond to young people experiencing homelessness with mental ill health. This involved consultation with young people with lived experience to understand how to improve access to stable accommodation and coordinated supports that built their capacity to live independently. We recommended personal plans for young people accessing the services and training for staff to support the holistic needs of young people.

Funders should invest in international models of best practice. As we noted earlier, Housing First models have been among the most internationally successful at improving long-term housing and mental health outcomes.

Studies across Europe, North America and Australia have shown these models can significantly improve long-term housing. A study of Canada’s housing-first model, At Home/Chez Soi, found those receiving housing-first support spent 41 per cent more time in stable housing over two years compared with people who did not receive support. For those with a higher intensity of needs, the housing-first model generated savings of around $21.72 for every $10 invested. While Housing First models generate great returns on investment, they do involve significant upfront costs.

Other housing models that aim to improve the living skills of people experiencing housing instability and poor mental health have also shown improved health outcomes. They have also delivered savings in the cost of bed-days of $74,000 and $178,000 by reducing the length of stay of people in community and acute mental health care units, respectively.

7. Use incentives and accountabilities

Leadership and structure should support sustainable solutions. Short-term funding contracts, lack of evaluations, and limited opportunities for showcasing effective interventions result in uncertainty for programs and inhibit sustainable outcomes. Key stakeholders across federal, state and territory governments need to play a coordinating role to improve mental health and housing outcomes.

This needs to start from ministers and government executives committing to change, holding people to account and incentivising the system (including through funding structures).

Cross-sector governance should drive the response, fostering collaboration between mental health and housing stakeholders at a federal, state and territory level. For example, the NSW Government’s Housing and Mental Health Agreement 2022 sets out an agreement between NSW Health and the Department of Communities and Justice. The agreement governs the interface between mental health and housing through policy, commissioning and service delivery. Joint governance structures should mean more than just meetings; they should involve clear purpose, roles and responsibilities, accountabilities, and escalation processes.

Representatives with lived experience of mental health and housing instability should be included in governance, including stakeholders from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to ensure strategies and initiatives are responsive to their needs.

The upcoming National Housing and Homelessness Plan is a step in the right direction. But the plan needs to ensure there is adequate support to address key intersections of people experiencing housing instability and homelessness, including mental health.

There is a strong imperative for action

Without urgent action, the number of people with mental health challenges who are homeless will increase.

The good news is that there are pockets of success, and there is a lot we can learn. Policymakers need to act now.

Get in touch to discuss how we can work with you on the intersection between mental ill health and housing instability.

Thanks to WentWest Primary Health Network and Youth Off the Streets for their support with the interviews and research that informed this article.

Connect with Holly Norrie and Steven Bothwell on LinkedIn.

Prepared with input from Tim Tucker.