Idea In Brief

Community needs

Strategic commissioning is a process for determining the services the community needs, deciding the role of government in providing these services, and designing the best service delivery system.

Starting point

Good commissioning requires putting in the effort in the first part of the cycle - identifying needs and communicating intentions. Get the first part wrong, and governments risk delivering a strategy that sets up purchasers for failure.

Key lessons

Drawing on our experience working with clients on these challenges, we have identified four key pieces of advice: Be clear about clients and outcomes; Think about the whole population; Use a system logic; Develop the right market strategy.

Picture this. You are working in a government agency that procures services from the non-government sector. Contracts are due to expire soon. Your department has recently published a new strategy that signals an intention for service system reform. Your agency is under financial pressure, and you increasingly need to provide evidence of value for money for procured services.

Your minister is taking a keen interest and is seeking a more strategic approach. Providers are telling you that demand is outstripping the funding available, and those not currently receiving funding are lobbying ministers for change. Members of the community are saying their needs are not being met.

So how do you make procurement decisions that can navigate through competing interests to deliver better outcomes, aligned with policy objectives?

Increasingly Commonwealth, state and territory governments, across portfolios ranging from health to social services, justice and defence, are embracing the concept of strategic commissioning.

Strategic commissioning is a process for determining the services the community needs, deciding the role of government in providing these services, and designing the best service delivery system.

It is easy to say but challenging to deliver. In recent years we have worked with many government clients to reshape service systems through strategic commissioning to deliver better outcomes for citizens. We are pleased to share some of what we have learned.

Strategic commissioning involves more than just procurement

While there is no single model for commissioning, experts have identified common processes (see, for example, The Public Policy Process and Purchasing for health) and many governments have developed their own commissioning models (such as Western Australia’s State Commissioning Strategy for Community Services 2022).

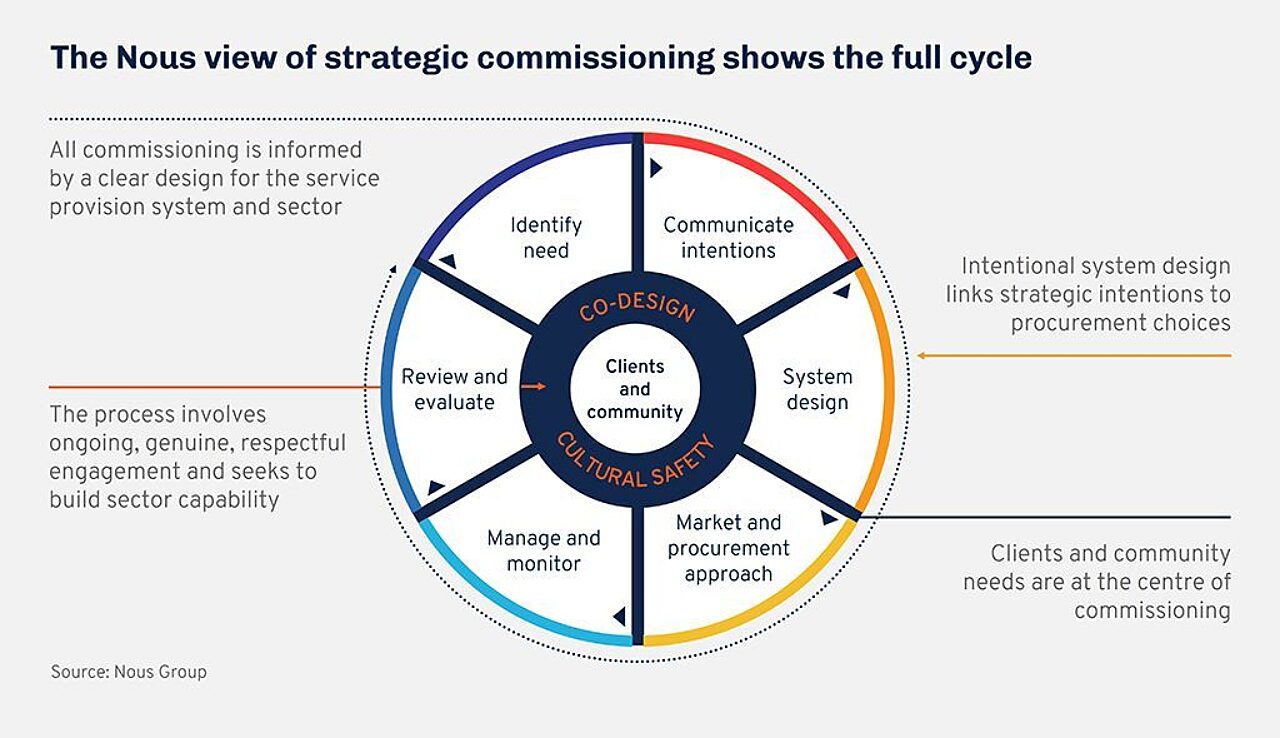

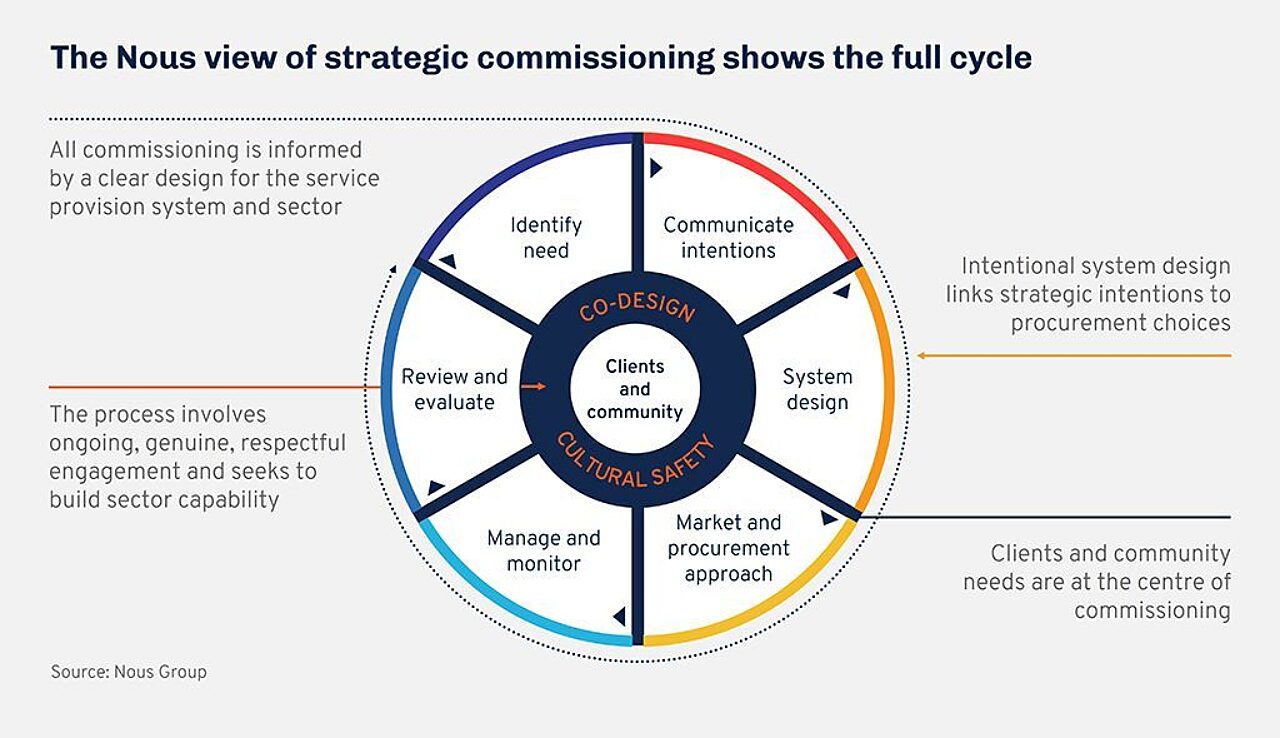

These commissioning models are usually described as a cycle. Our take on the commissioning cycle places clients and the community at its centre and emphasises system design as a critical step to ensuring strategic direction translates into procurement decisions.

While the traditional view of commissioning started at the procurement phase, then moved to management and monitoring, we believe using this as a starting point misses a vital step.

Good commissioning requires putting in the effort in the first part of the cycle (identify need, communicate intentions). Get the first part wrong, and governments risk delivering a strategy that sets up those doing the purchasing for failure. Having a strategy that is disconnected or fails to influence procurement processes is no better than having no strategy at all.

The latter part of the cycle may feel uncomfortable for many service systems. Achieving deliberative system and service design, and designing a market approach that reflects market conditions, requires government to do things differently. Government agencies may not yet have the capabilities or may be unsure where to start.

Four tips for turning strategic commissioning into reality

So how do you put this into practice? Drawing on our experience working with clients on these challenges, we have identified key pieces of advice:

- Be clear about who your clients are and what outcomes you are seeking.

- Think about the needs of the whole population not just current users.

- Use a system logic to link system features with better outcomes,

- Develop the right market strategy for the system you want.

1. Be clear about who your clients are and what outcomes you are seeking

It is essential for strategic commissioning to be anchored in client outcomes and experiences. To start, identify who the clients of the system are, and the outcomes we want for them and the system they access.

A conversation about who the clients of a system are will define success from the outset. It will also help with resourcing decisions down the line: should the focus of the system be on intensive services for a small number of people, or less intensive services for a larger number?

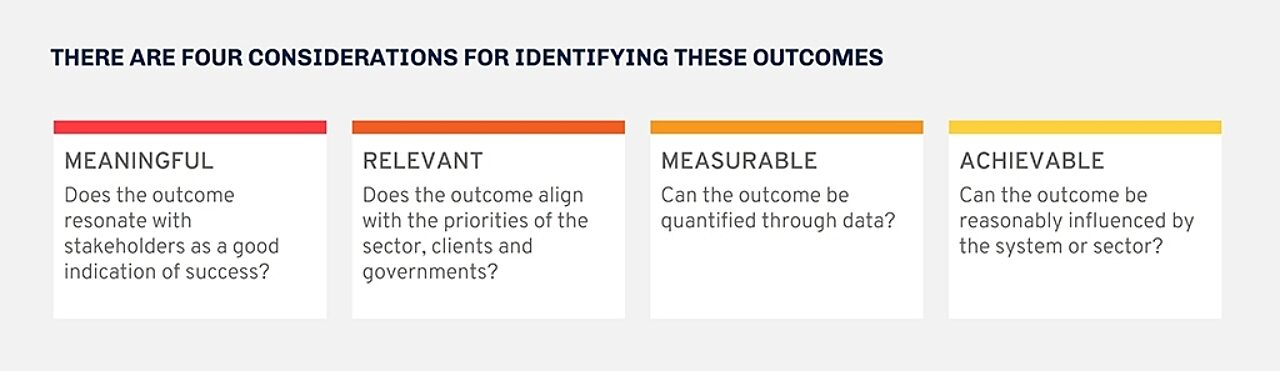

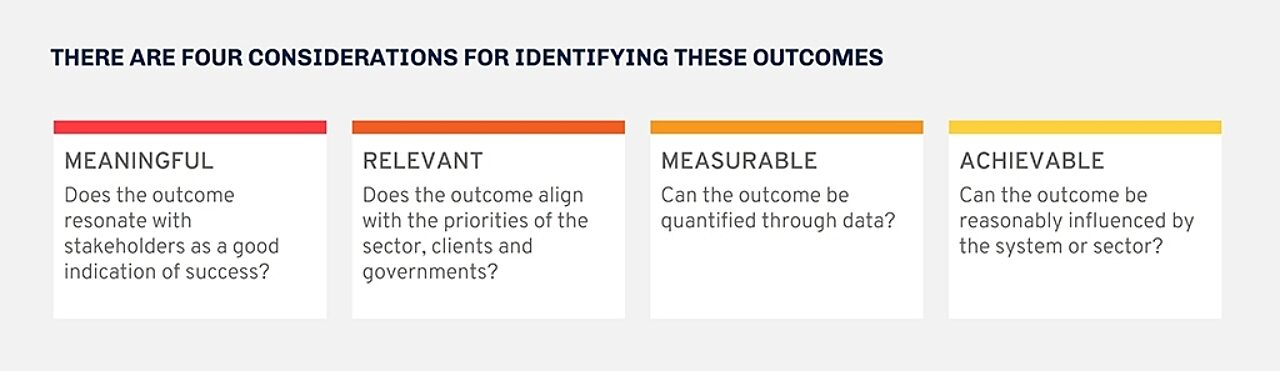

Outcomes are clear high-level statements that describe what success looks like. They can be divided into person-centred outcomes (for example, individuals access the right legal assistance at the right time) and service and/or system outcomes, which might include provider sustainability, capacity, and capability considerations.

Case study

2. Think about the needs of the whole population not just current users

The next step is to think carefully about user needs. Methodologies to assess need should where possible:

- be epidemiological. Break down the population of potential service recipients into cohorts, stratified by factors such as age group and level of service need. Allocate proportions of the population to each group.

- be comprehensive. Use a standardised service taxonomy to capture different types of services that should be available.

- be captured in service profiles. It is necessary to understand the services that different cohorts need, grounded in engagement with the relevant sector. This engagement can be useful to build and test assumptions about the optimal service response for cohorts with varying characteristics and in different regions. This process can take time, but the investment is worth it.

- be modular. Bring these elements together to estimate true need in a way that can be broken down by region, by cohort, or by service type.

Case study

3. Use a system logic to link system features with better outcomes

The next challenge is to identify what the service-delivery system should look like. This can mean defining system criteria or features, which collectively describe the principles of a well-functioning system. Where data on needs and services is more mature, identification can mean specifying desired service volumes (service levels) and the design of specific services (service standards). These are typically done by region, by cohort group or by service type.

Once this is done, you are set to identify gaps and priorities for future investments that address unmet need and move toward an optimal system.

We have found the best way to link this together in a simple, compelling way is using a system logic model. A system logic model provides a schematic representation that describes how future investment priorities will support a desired future-state service system, which in turn contributes to better outcomes for clients of the system.

Case study

4. Develop the right market strategy for the system you want

What is the right procurement approach to optimise the system of services and outcomes while delivering value for money? This will depend on the nature of service delivery and the state of the market and its players.

There are many options for putting government activities or services on a contestable footing. These are reflected in our Contestability Ladder, where procurement approaches at the top of the ladder represent highly contestable markets.

No one approach is necessarily best. In a well-developed market with multiple suitable providers (a ‘thick’ market), competitive tendering with an emphasis on value for money is a good strategy. But this strategy is much harder to get to work in thin markets, where a better approach is involves building capacity and bringing in new providers. In those circumstances a better commissioning strategy is one that that includes partnerships between established and new providers to develop a stronger local capacity, or factors in the cost and lead time for new entrants to get established.

Another factor to consider in developing the right go-to-market approach is risk. Staying with known providers can be less risky for performance and service continuity. Changing to a new provider involves the risks that they may not be able to perform and that clients may experience service interruptions or be unhappy with losing their established relationships with existing providers. There can also be political risks with defunding providers.

Strategic value for money will also play a role. There will almost certainly be more demand than funding available to commission services. The challenge is to design the commissioning to best meet community need and policy objectives.

There are typically upper and lower limits on the degree of contestability a government department can entertain. Values, politics and efficiency each play a role. These must be factored into where on the staircase a commissioning process sits.

Agencies are under pressure to act

Many state and federal agencies that commission services are under growing pressure from ministers and central agencies to deliver evidence-based value for money.

In designing a strategic commissioning framework, it is essential to think about more than procurement. Agencies would benefit from practical insights to fill the gap between policy and better outcomes for individuals and communities.

Get in touch to explore how we can help you to undertake strategic commissioning.

Connect with Claire McCullagh and Grace Hutchison on LinkedIn.

Prepared with support from Tanya Smith and Ian Thompson.