Idea In Brief

Research strategies can be effective, but too often flounder

While they are recognised as important for advancing a university's mission, their effectiveness varies greatly in practice.

Strategic choices require consideration of multiple components

Making these choices in a university isn’t easy, but in a financial constrained environment it becomes increasingly necessary.

The strategic plan is as important as the final document

Engagement in the strategy process is equal parts about bringing together input from diverse stakeholders and building buy-in.

Most universities have a research strategy, reflecting the need to bring a level of coordination to research activity to maximise impact. While research strategies are generally recognised as important for advancing a university’s mission, in practice their effectiveness varies greatly.

Some strategies prove to be genuinely transformative, driving exceptional outcomes and progressively boosting research impact over time. Others falter at the starting line, failing to gain meaningful traction or becoming little more than symbolic gestures. And all too many research strategies achieve only moderate success, hindered by a lack of focus, clarity, or engagement from the research community.

Defining strategic priorities

A foundational question for any university regarding research strategy is the extent to which it should guide the overall agenda versus enabling a more organic approach to research activity. While the “let a thousand flowers bloom” approach is the preferred approach for many a researcher, the reality is that it has only ever been a viable strategy for a minority of institutions, typically those with exceptional scale, prestige, or endowment. In today’s environment of constrained funding, heightened accountability, and increasing demand for demonstrable impact, that minority is shrinking. For most universities, a more deliberate and coordinated approach is not only justified but essential. The below assumes that some level of strategic agenda is necessary.

From our work with universities and other research institutions there are a set of clear steps to maximise the chances a research strategy will actually be effective.

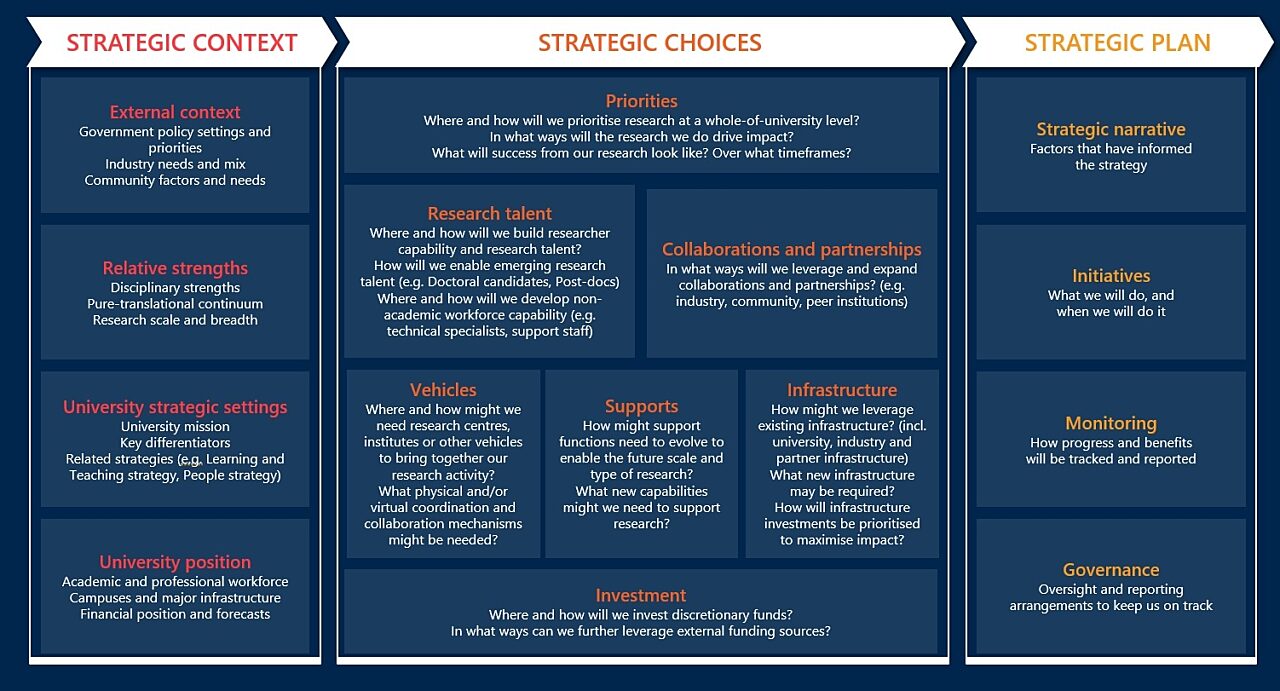

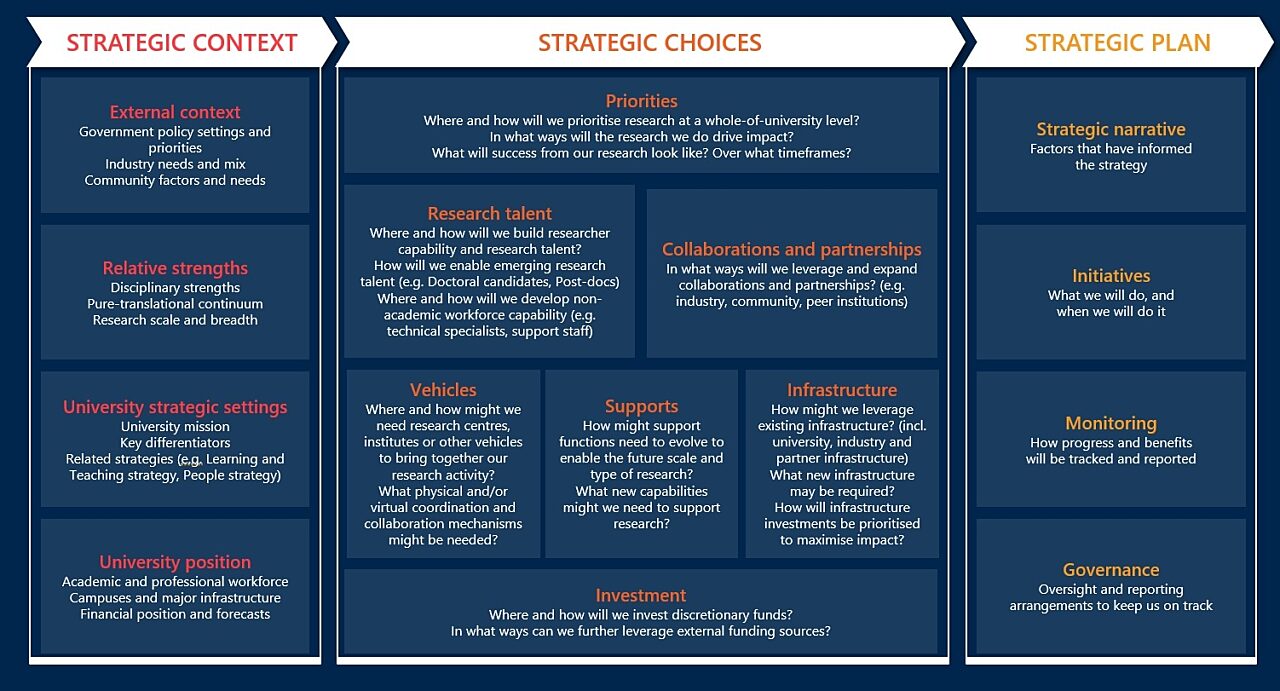

The diagram below is a useful framework for planning how to develop a research strategy. As illustrated, this involves three broad stages: an initial exploration of the strategic context which informs strategic choices, which are captured and realised through a strategic plan. Each of these is discussed in more detail below.

Strategic context: Start with a detailed understanding of what the university is great at and broader contextual factors

A common challenge in starting the journey to a new research strategy is understanding what the university is merely good at, and where it is truly great. There are multiple challenges that need to be addressed to bring about sufficient clarity on this. The considerable time lag between research activity and real-world impact can make it difficult to understand where to double down on areas of great potential, or where an area of research is actually in decline. Combined with this, every researcher will highlight the great work they and their teams have done and the impact they have. They are proud of the work they do, and rightly so, but this can obscure a more objective view of the relative performance of different disciplines and research areas.

Getting a clear sense of what the university is actually good at relative to peers is very important. This means digging into the various research performance data that are available, and doing so at a suitably granular level to understand both the big picture and draw out the weak signals that demonstrate opportunity for growth or risk of relative decline. This involves using data to understand and evidence which disciplines and sub-disciplines are strong and which less so; the spread of research performance across the academic workforce; and the volume and quality of research outputs in all their forms, including papers, publications, conference presentation, licences and spinouts.

Understanding this baseline should be complemented with an assessment of external factors such as government policy priorities, industry and partner needs, and community expectations. This context is crucially important to understand where there may be need and future funding available to expand or reprioritise research activity. Mapping this to disciplinary strengths can be a powerful way to demonstrate new and emerging areas of opportunity, existing strengths to double down and build on distinctive strengths, and areas that may need some form of renewal and rejuvenation.

It is crucial that a research strategy aligns with other strategy documents. It should clearly cascade from the university’s overall strategic plan, bringing research to bear in ways that support the overall mission and reinforce aspects of differentiation and culture. It also needs to demonstrably align with other strategy documents. This will vary by institution, but would most commonly include the Teaching and Learning Strategy, to bring maximum effect to research led teaching and to recognise the dual teaching and research aspects of academic careers. Other relevant strategies and plans may include workforce strategies (in particular regarding academic capability development and workload/resource allocation), campus master-planning and partnership strategies.

Research strategies inherently require considerable engagement across the university community. Consolidating key findings from the above into a readily digestible document can be of enormous value in progressing engagement and inviting input to the strategy development, establishing a basis for helpful debate and framing discussions in ways that focus in on key strategic choices.

Strategic choices: These choices are necessary, and generally include consideration of multiple components

Strategy is about making choices about where and how to focus in ways the deliver disproportionate benefits. Making these choices in a complex organisation such as a research-intensive university is not easy: the sheer breadth of academic endeavour can it challenging. Debates can easily lead to false choices, for example between fundamental and translation research, or playing one discipline off against another in ways that lead to distrust more than agreement. In the context of academic freedom, there can also be questions about the extent to which the institution should and can make choices. Yet there are clear benefits in an effective research strategy, particularly in an environment of limited funding, to maximise impact.

For the strategy to result in improvement, the strategic choices made need to have some tangible effects. These will frequently be a mix of: changes to resource allocation; shifts in levels and types of collaboration; changes to workforce over time (e.g. recruitment, size and shape of different areas); clarity of narrative and signalling, both internal and external. If these changes or similar do not come about as a result of the strategy, then its utility is likely to be limited.

One common pitfall in research strategy development is trying to deliver something for everyone, resulting in diluted objectives that sidestep the all important issue of making difficult trade-off decisions. A related challenge is the reliance on grand challenges or frameworks such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to focus attention. This approach all too often falls short as the vast majority of university research falls within these very broad agendas, again sidestepping the need for trade-off decisions. Effective research strategies must also reflect the financial, cultural, and contextual realities of the institution, including the expectations of the researcher partners, funders and local communities. Ultimately, a research strategy’s success hinges on its ability to galvanise the researcher community in ways that drive research quality, activity, and impact.

In our experience, the strategic choices that make up a research strategy can be considered as follows, noting that they may be combined or presented differently in the final research strategy document.

Research priorities

It is usually helpful to establish priorities that guide where and how the university as a whole will focus effort. Priorities can and should inform where the university invests, provide additional coordination or otherwise supports specific aspects. This may be in terms of expanding academic capacity in particular areas, growing capability in ways that drive impact in various forms (e.g. industry collaboration or entrepreneurship agendas), or some other mechanism to bring about some level of focus.

It is important to note that priorities are intended to provide a level of focus, but they are not exclusionary. They should not attempt to block academics from pursuing the research they consider most beneficial; indeed if they were to do so the resulting strategy would be unlikely to be long term effective and sustainable, tending towards stifling rather than enabling innovation and the generation of new knowledge.

Research talent

Academic capability underpins a university’s research endeavours, and an effective research strategy needs to consider where and how to enhance and sustain academic talent. This is much more than considering research development programs, even though these can play an important role in research capability. It also considers aspects such as strategic recruitment to expand or create new areas of strength, approaches to allocations of fellowship funding, post-doctoral opportunities and PhD scholarships in ways that expand academic talent where it would be most valuable.

It also needs to consider broader workforce planning matters, such as mechanisms for researcher succession and talent planning. In addition to researchers, specialist technical support capabilities, such as laboratory technicians, technology transfer experts and research grant proposal specialists also need to be considered. Challenging questions may also need to be addressed, such as whether to replace academic talent lost through natural attrition in areas of lower research priority, or the relative balance of teaching and research time allocations.

Collaborations and partnerships

In developing a research strategy it is useful to consider how the university will enable and focus partnerships and collaborations in ways that deliver strategic benefit. This may be in terms of the types of partners the university will aim to collaborate with. For some universities, particularly in highly ranked universities that are more focused on fundamental discovery research, priority might be given to partner with other universities of a similar global ranking. For others, it may make more sense to collaborate with other institutions that share common aspects of geographic or community contexts. Some universities may opt to be much more focused on industry partners, particularly for research translation and contract research. It is also possible to blend these ideas to some extent, so long as it is clear where and why certain types of collaboration and partnerships are preferred to others.

As discussed above, this does not preclude academics collaborating with colleagues and industry where this makes sense for the research they undertaken. It can and should inform where the university as a whole invests discretionary time and effort, without impinging on academic freedom.

Vehicles

Research vehicles come in many forms, shapes and sizes, from small high-impact research centres operating out of a single office through to large scale institutions combining the efforts of thousands of academics, industry and community partners in bespoke facilities. Some vehicles will have a distinct physical aspect, particularly when specialist research infrastructure is required, while others will be purely virtual mechanisms.

Research vehicles can be powerful ways to bring together research capabilities in ways that deliver disproportionate impact, and as such they can be a powerful mechanism for realising benefits from a research strategy. It is also important to recognise that research vehicles do have an effective life: some may be very long, others much shorter. Considering where a research vehicle has run its course and where some form of renewal is needed is helpful in working through a research strategy to make sure that any investment in research vehicles delivers the maximum impact possible.

Supports

There are a wide range of support functions that enable research. From the technical support needed to keep specialist research equipment operational to research contracting advice, accelerator programs, pre- and post-award support functions, there are diverse capabilities that are helpful to consider as part of strategic planning. Benchmarking of support services undertaken in the Strategic Context phase can helpfully inform where improvement opportunities may exist, including in functional resourcing and in process and system effectiveness. Strategic choices about where and how to focus improvement effort in support functions needs to align with the other strategic decisions discussed above.

Infrastructure

A key consideration in research strategy development is how to focus investment in research infrastructure. Usually, the demand for new research infrastructure exceeds what is realistic within available budget and timeframes. At the same time, having suitable research infrastructure available can make or break various aspects of strategy, so working through where to invest needs to be done in parallel with the broader of research priorities. Considering research infrastructure is as much about working through how to best leverage existing infrastructure (such as labs, buildings and equipment) and external infrastructure (national research facilities, collaborations with and access to peer institution and industry facilities) as it is about new investments. While much focus is put on physical infrastructure, in practice the exponential growth in digital research infrastructure (such as high performance computing, AI access, data and networks, specialist software, etc.) means this needs to have a similar level of focus. And both physical and digital research infrastructure aspects need to consider the technical workforce necessary to operationalise any investment made.

Investment

When making investment decisions, universities need to consider multiple factors. Unlike publicly listed companies that rely on financial metrics such as Net Present Value (NPV), universities must consider a broader and more nuanced set of criteria when making research investment decisions. These may include research quality and impact, alignment with institutional mission, contribution to societal or economic outcomes, potential for future funding, and capacity to build distinctive capability. Clarifying these criteria upfront helps ensure that strategic choices are both intentional and defensible.

In a financially constrained environment, being clear about where to invest is of critical importance to bring a research strategy to life. In practice, there is likely limited funds available to support new initiatives and investment, yet without some funds any new strategy is unlikely to gain traction and deliver change. Understanding where and how to invest also requires consideration of the various impacts that the university is aiming to achieve, and various criteria that can be used to inform investment trade-off decisions. These criteria can include varied aspects such as measures of research quality and volumes; contribution to economic and societal outcomes; research collaboration potential; or commercialisation measures. The specific criteria should align with and cascade from the broader strategic objectives.

Rather than spreading what limited funds there are broadly across the institution, there is value in being targeted in ways that drive disproportionate benefits. This might be through co-investment between central and faculty teams, and with industry. As discussed above, targeted fellowship programs and PhD scholarships can be powerful ways to nudge research activity in ways that better align with defined priorities. Competitive schemes for research vehicles to access central funding pools can be a useful mechanism, incentivising vehicles to tap into external funding sources while also investing in those that are well aligned with priorities and have demonstrable future potential.

Strategic plan: The research strategy should contain some key components, but the process for developing it is as important as the final document

The final research strategy is an important document that guides institutional decision making for years to come. The actual form of the document itself varies, but generally includes:

- a broad narrative outlining the key factors that have informed the strategy, including the institutions context and achievements, the role of research in delivering on broader institutional mission, and external contextual context that have shaped strategic choices;

- the priorities and initiatives that will be progressed to deliver on the research strategy, and the broad approaches, timelines and accountabilities for delivering them;

- the measures and mechanisms for monitoring and reporting on progress and tracking benefits; and

- the governance and oversight arrangements that will be used to keep the research strategy on track, including mechanisms for collaboration across the institution and with external partners.

While the final research strategy is an important and powerful document, the process through which it is developed is just as important. In practice, developing the research strategy is equal parts about bringing together input from a diverse array of stakeholders (including researchers, university leaders, industry partners and higher-degree research candidates) and building buy in for the future research strategy. As such, engagement in the strategy process is as much about change management as it is about strategic thinking, and needs to be planned as such. It is well worth considering in detail factors such as:

- How can the researcher community best be involved in the process, both to provide input and to bring them on the journey?

- What formats are going to be most valuable for engagement activities to achieve both the necessary input and help the change journey?

- What key messages, pre-reading and supporting materials will help engagement activities be most impactful and valuable?

- Who is best placed to lead different engagements, considering both optics, capabilities and leadership responsibilities?

- How will the research community be kept informed throughout the process of developing the research strategy?

- Who needs to be included in oversight of the research strategy development process, both from the perspective of their expertise and leadership role, and from the perspective of their future ownership of different aspects of the strategy itself?

- Each of these factors can be readily addressed through careful planning upfront.

A well-crafted research strategy is more than a document. It’s a catalyst for institutional clarity, alignment, and momentum. By grounding strategic choices in evidence, engaging the research community meaningfully, and aligning with broader institutional goals, universities can unlock the full potential of their research endeavours. The process of developing the strategy is itself a powerful opportunity to build shared purpose and commitment. Done well, it sets the stage not only for enhanced research performance, but for deeper impact.

Get in touch to discuss how your university can craft an effective research strategy.

Connect with Peter Wiseman and Matt Durnin on LinkedIn.

This article was co-written by Simon Lancaster during his time at Nous.