insight

At Nous, we believe in the sustaining power of great organisational leadership. Over the past two years, we have launched the Nous Leadership Way (NLW), a leadership model and development program that articulates the core principles of effective leadership at Nous. Developing NLW has prompted Managing Principal and CEO Tim Orton to think more broadly about the challenges of great leadership, the attributes of great leaders, and how we think about these at Nous.

High performing and successful teams across many domains – sport, business, politics, you name it – often share many attributes: clear vision, good strategy, raw talent, a strong work ethic, a collaborative culture.

But what separates the truly great teams from the merely good ones? One important factor – in some contexts I would argue the most important factor – is how they handle pressure. Good teams cope with pressure (they do not collapse under its weight like mediocre teams). Great teams, however, thrive under pressure. They are motivated by it. The stress that comes from pressure cooker situations creates a sense of urgency that heightens focus, concentration and commitment, and ultimately improves performance.

At Nous, we recognise the motivating power of stress (for both individual Nousers and as an organisation) and seek to be strengthened rather than diminished by it. As such, eustress is one of thirteen tenets of the Nous Leadership Way – our organisation’s leadership model and philosophy. A term used by psychologists since the 1960s, eustress refers to a positive cognitive response to stress. It arises when one is stretched and pushed slightly beyond their comfort zone but not overwhelmed.

Aspire to eustress: Where stress is viewed as a challenge rather than a threat

As with many unfamiliar concepts, sport provides a good way to understand eustress.

Sports scientists often talk about the Challenge vs Threat Mindset. This refers to two ways that athletes can perceive and respond to high-pressure situations. They can view such situations as an opportunity to grow and showcase their abilities (the Challenge Mindset), or they can view them as insurmountable obstacles (the Threat Mindset).

This idea will be familiar to any sports fan. Athletes and teams that rise to the occasion and consistently win close games under pressure take a Challenge Mindset. By contrast, teams that collapse under pressure, those that falter or choke when the going gets tough, take a Threat Mindset.

The Challenge Mindset epitomises eustress, while the Threat Mindset exemplifies distress. Eustress arises when a stressor is seen as a positive challenge rather than as a threat. When one experiences eustress, the goal in question is slightly out of reach, but it remains in sight.

Eustress is a property of both individuals and organisations. Just as individuals face stressors – a tight deadline, high stakes meeting, difficult stakeholders, etc. – so too do organisations, for example in the form of challenging market conditions, exogenous demand shocks or an increase in competition. Such factors can spur businesses towards higher performance and more innovation, or they can lead to sclerosis, stagnation and decline.

Eustress is an empowering idea – which is why we emphasise it at Nous. It reminds us that while stressful situations are an inevitable fact of our professional and personal lives, how we respond to them as individuals and organisations is up to us.

Eustress is a Goldilocks zone

This is not to say that any amount of stress in the workplace can be a good thing if only we can rise to the occasion. Like many things, it is a good best enjoyed in moderation. An excess of stress can be associated with a range of negative experiences – the state of being overwhelmed, nervous, anxious, or (in extreme cases) burn out. By contrast, a dearth of stress can be associated with feelings of indifference, apathy and ennui. These are often much worse than stress – both for the person involved and their colleagues. When we are under-stimulated or under-motivated, we do not perform at our best and develop slowly, if at all.

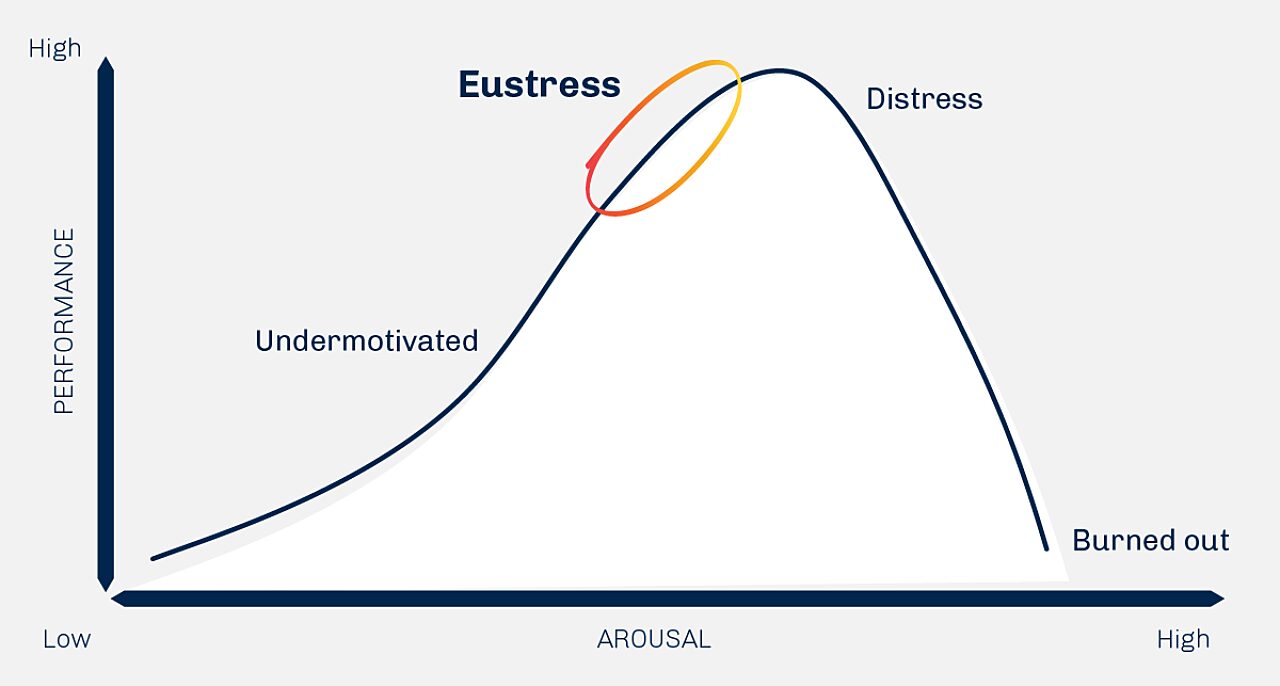

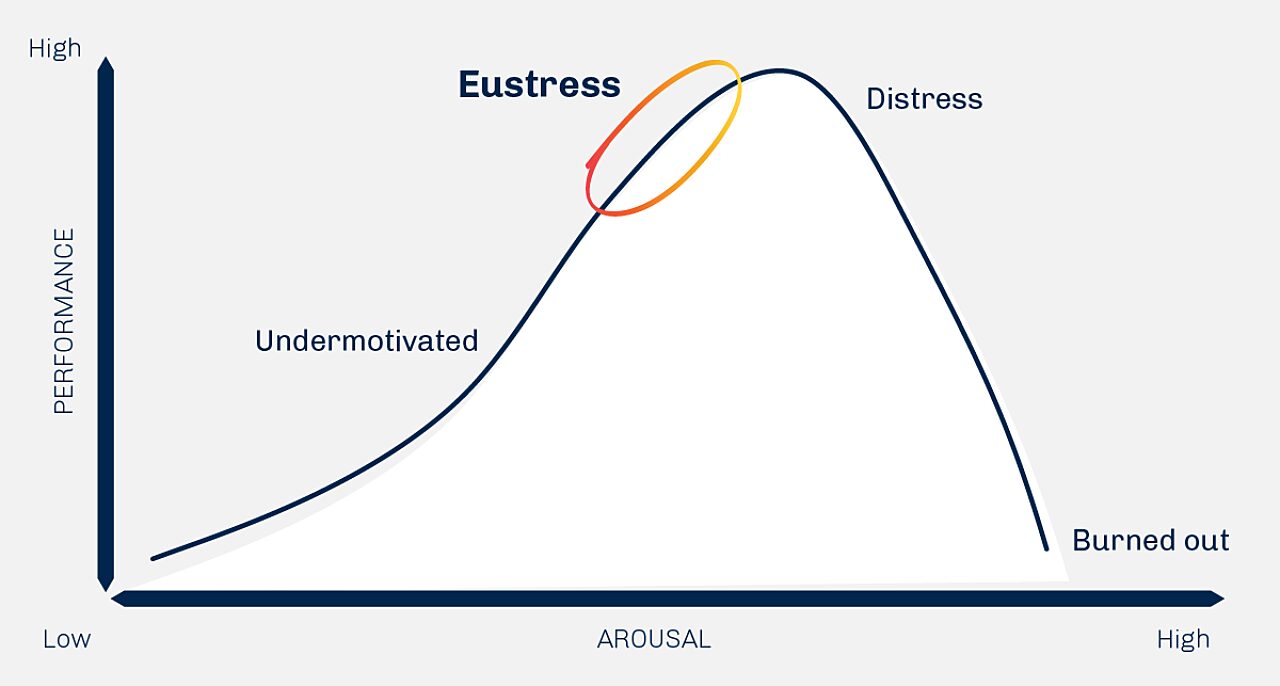

I like to conceptualise eustress in terms of the Yerkes-Dodson law, an empirically observed relationship between levels of arousal and performance in a task (see Figure 1). The U-shaped curve reflects the intuition behind Eustress. When one is under-stimulated, their performance will tend to be low. More stimulation or arousal will tend to increase performance, but only to a point. But if there is too much demand on us, we risk going past eustress to distress.

The challenge for individuals and organisations, then, is how to achieve the Goldilocks Zone of Eustress. This is where leaders step in.

Leaders should cultivate and demonstrate eustress

In my experience, the optimal point of eustress is not some natural equilibrium that a workplace happens to stumble on. Indeed, often organisational cultures tend to promote sub-optimal levels of arousal in their colleagues – either under-stimulation (apathy, ennui) or over-stimulation (panic, burnout).

Leaders need to actively create the conditions that enable their colleagues to consistently operate at or around the point of Eustress. If they are under-stimulated, leaders need to raise demands to create more stretch opportunities for them. If they are over-stimulated, leaders need to reduce the demands and moderate their stress to return to the point of peak performance.

This requires leaders to be attentive to and aware of their team members’ experiences. Every individual has a different zone of eustress and responds differently to different kinds of stressors. Moreover, if people have a positive experience of stress in the past, their zone of eustress will tend to shift right over time.

Leaders can thus grow (both in themselves and in others) a capacity to constructively absorb more stress over time. To achieve this, leaders must exercise emotional intelligence to cultivate eustress in the people that they lead – recognising their unique characteristics and their capacity for growth and change.

It also requires leaders themselves to model eustress by demonstrating a positive level of stress in their day-to-day work. On the one hand, this should involve role modelling calmness (after all, a frenetic approach to leadership is a sure-fire way to lose the confidence of one’s colleagues). On the other hand, this should involve being up front with colleagues about what is required to maintain calmness. A person treading water usually needs to work hard to stay afloat. The hard work going on below the surface is not often readily apparent to others. A good leader should show their colleagues what is required below the surface to maintain calmness and coolness above the water.

In these ways, workplace stress need not lead to panic or paralysis among those that experience it. Rather, leaders can model and cultivate the organisational contexts required to achieve a level and quality of stress in workplaces that promotes the healthy buzz of high performance.

Get in touch to discuss how you can model and leverage eustress in your organisational context.

Connect with Tim Orton on LinkedIn.

This is the eighth article in Tim Orton's 'Exploring Great Leadership' series. It was originally posted on LinkedIn on 2 September 2025.

You can read the previous article in the series here.