Idea In Brief

The days of eternal growth in higher education are over

University leaders must now consider what kind of growth is right for their institutions, focusing on financial sustainability and market orientation.

Universities must learn to support equity students better

This involves designing effective support services and using data analytics to predict and intervene when students are at risk.

Offering a full complement of courses presents risks

Universities must balance financial returns with their mission to provide public good, ensuring courses are streamlined and interdisciplinary.

Last month’s launch of the interim Australian Tertiary Education Commission (ATEC) is a reminder that the days of eternal growth in higher education are all but over. Though somewhat less constrained than first imagined, the introduction of a managed system means that university leaders need to consider what kind of growth is right for their institutions.

Which students are they best placed to serve and in what ways? What might need to change across the suite of courses offered and how they are constructed? And, critically, how do universities become more oriented to the market and bolster the fundamentals of a university education – that is, person-creation and capacity-building?

Posing and answering these questions in a managed growth environment is now a necessity, not simply because financial sustainability depends on it, but because governments, students, and societies are asking for this like never before.

The question of whom to serve

Many universities have admirably committed to educating more students from so-called equity backgrounds. There are plans in place to attract more students from regional locations, students from disadvantaged backgrounds, First Nations students, students with disability, and so on. Indeed, the ATEC’s commitment to needs-based funding is designed to enable exactly this. But careful thought needs to go into the design of support services as well as the way in which a curriculum is taught, to enable retention and student success on par with non-equity peers. Retention rates for all students fell slightly from 2016-2022, but more so for equity students, where only 80.1 per cent were retained from 2022-2023, compared to 85.7 per cent of their non-equity peers.

The answer perhaps is to draw more on what other sectors do to support and enable people from these backgrounds, which is to have a person-centred approach, clear risk indicators, and alternate measures of success where these make sense. The introduction of AI capability could not be more timely in this regard: never before have we been able harness data in a way that can predict when and how we might need to intervene when students are at risk. For example, Northumbria University ran a recent pilot that used learning- and wellbeing-related analytics to surface students showing early signs of mental-health or engagement risk, enabling targeted wellbeing support and informing practical improvements in outreach. Similarly, Arizona State University has continued to expand analytics-led approaches that combine LMS and administrative data so advisers and teaching staff can prioritise outreach and redesign supports at the course level, helping to target interventions earlier and more effectively.

Whatever the approach, it bodes well for universities to understand the various archetypes of learners and students, with academics working closely with their marketing and analytics teams to paint rich pictures of their current and prospective learner needs.

The question of what to offer

Australian universities are comprehensives and there is strong argument to say they always should be. Why should a student in a certain location not be able to study what they want in their hometown? Time will tell if there is an opportunity for universities to collaborate on collectively meeting the needs of learners by offering complementary courses. But, in a managed system, offering the full complement of courses presents risk if not carefully thought through. In the very recent past (and some would argue at present), it was easier to compensate for offers that had lower student numbers by boosting places in courses with higher demand. When this involved international students, the result was a financial surplus that could be invested in research, course quality, professional services, and more. The risk now, of course, is that if we have a finite number of students, international or otherwise, the pressure will be to prioritise those courses that deliver better financial return, which can lead to decisions that are antithetical to the university mission.

How does the sector strike the right balance here? On the one hand, there is the grim reality of less money for jam, and on the other is the mission-critical pursuit of offering courses that are about the public good, no matter the returns. The answer, we think, lies in the careful construction of offers, the smoothing of edges to create streamlined courses without excessive numbers of units or majors – let’s remember that students want flexibility, not endless choice – the sharpening of courses so that the value they provide in person-creation and career-readiness is pointed, and the interdisciplinarity of offers so that there is little duplication of effort across the many schools and faculties.

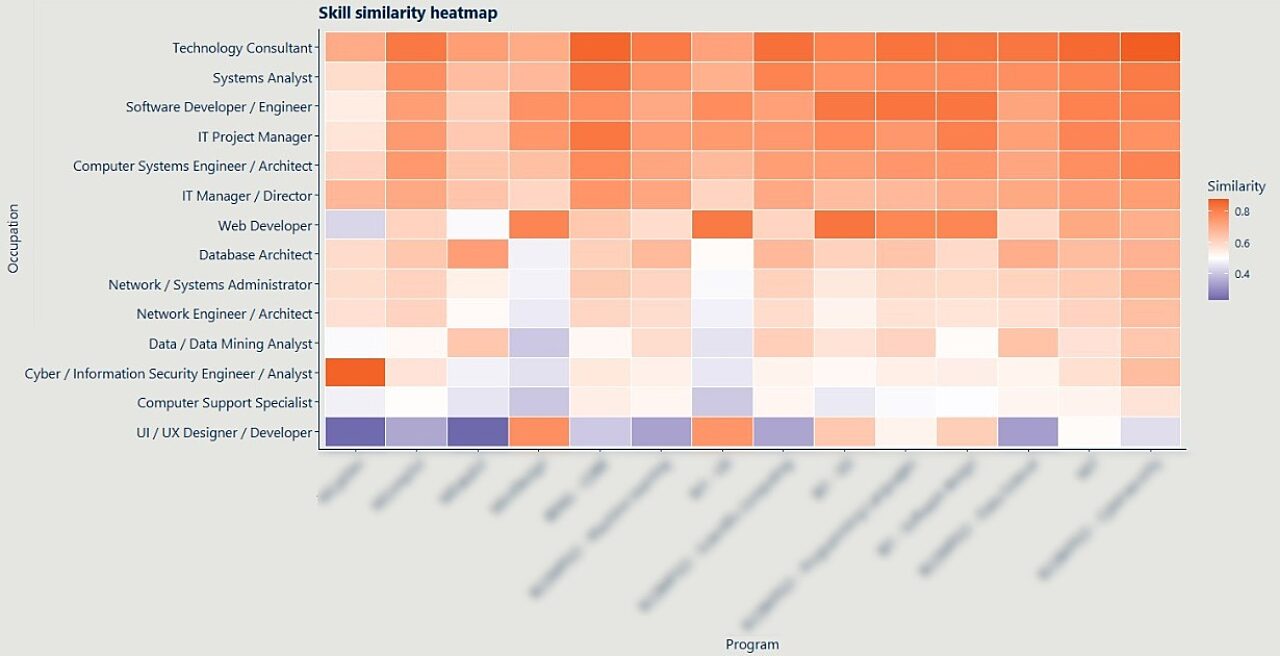

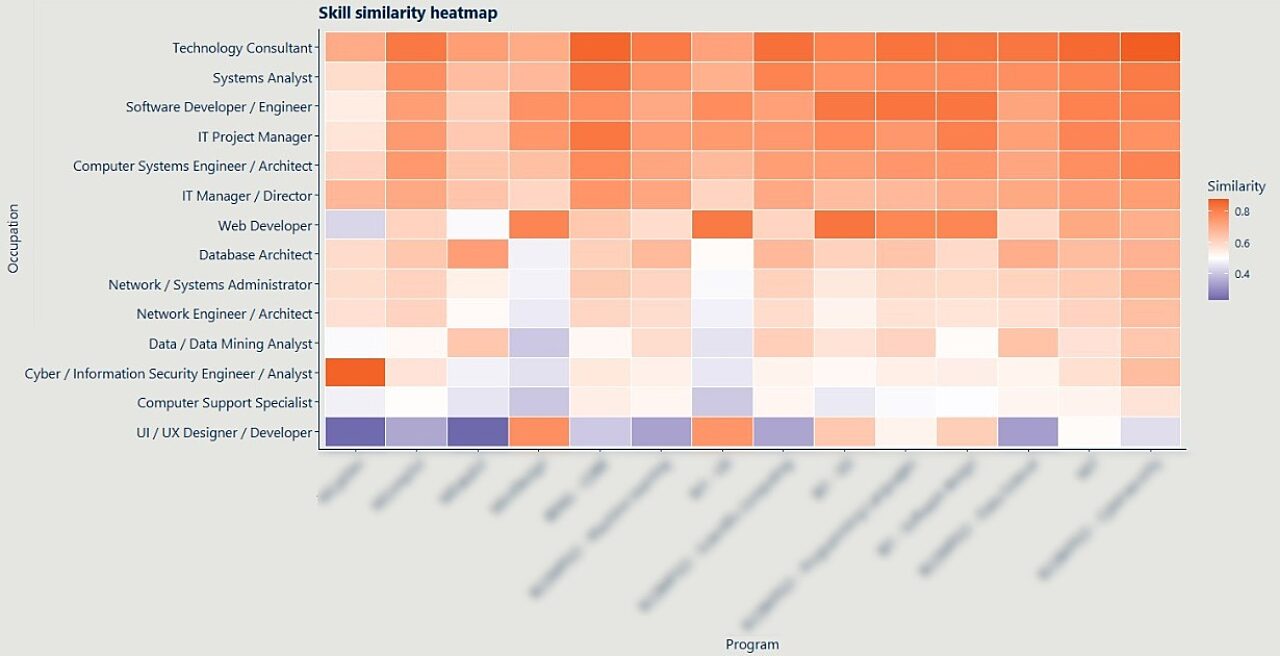

Some duplication even exists within single faculties and schools, and not by design. The result can be confusion for prospective students and inefficiency for academics, who could otherwise use their time for research or to enhance the quality of their programs. The image below is an example of similarity analysis we’ve conducted – in this engagement with a university faculty, the heatmap helped academics to redesign course components to reduce duplication and also to plug gaps in the offer.

But how do we make such determinations? The answer partly lies in the data, but mostly in ‘sense-making’. This is when professional and academic staff come together to review data and intelligence and understand where an offer’s gaps exist: “There is increasing demand in law and international relations. How feasible is a double-degree or a major/minor that satisfies this demand?” It’s also about recognising when a course may benefit from renewal or reimagining: “We're seeing less demand for Physics. What contemporary applications could strengthen its relevance and appeal?” And, at times, it involves making considered decisions about the future of a course: “Does this offering still meet the needs of students and the sector?”

The question of how much growth is good

We talk endlessly about efficiencies and effectiveness of scale. But what does this mean in a managed market? The answer is obvious: it depends.

Here is where universities have the opportunity to be truly distinct and to develop the balanced growth strategy that is right for their mission, their students, their staff, and their communities. The intricate balance of cost, revenue, quality, and values must be modelled – one would argue on more than an annual basis – and the outputs of this modelling deeply discussed with decision-makers and others invested in the mission of higher education. We will discuss measurement and its increasing importance in a future article.

There is a sweet spot to be found where mission and margin are not competing priorities but rather the fundamental principles that allow universities to continue to be societal pillars with solid foundations.

Get in touch to discuss how your university can pursue purposeful growth in a managed higher education market.

Connect with Christine Samy on LinkedIn.

This is the first in our three-part series on university growth in the managed era. Future articles will focus on student experience and how we measure it.