Idea In Brief

Strong global momentum

Product stewardship has become a common policy response around the world to improve waste management and support the transition to a circular economy. It is especially useful for emerging and fast-growing waste streams.

Unrealised ambitions

Australia has intended to enhance product stewardship for over a decade, but the legislative scheme has not been as effective as it could be in changing industry behaviour and improving end-of-life product management.

First principles

Product stewardship schemes need to be suited to their context. To establish the right kind of scheme, governments need to consider to what extent market forces can be relied on to improve waste management across a product’s lifecycle.

In the race to deal with the environmental costs of increasing levels of waste generation and pollution, ambitious targets set by governments must be matched by ambitious policy responses.

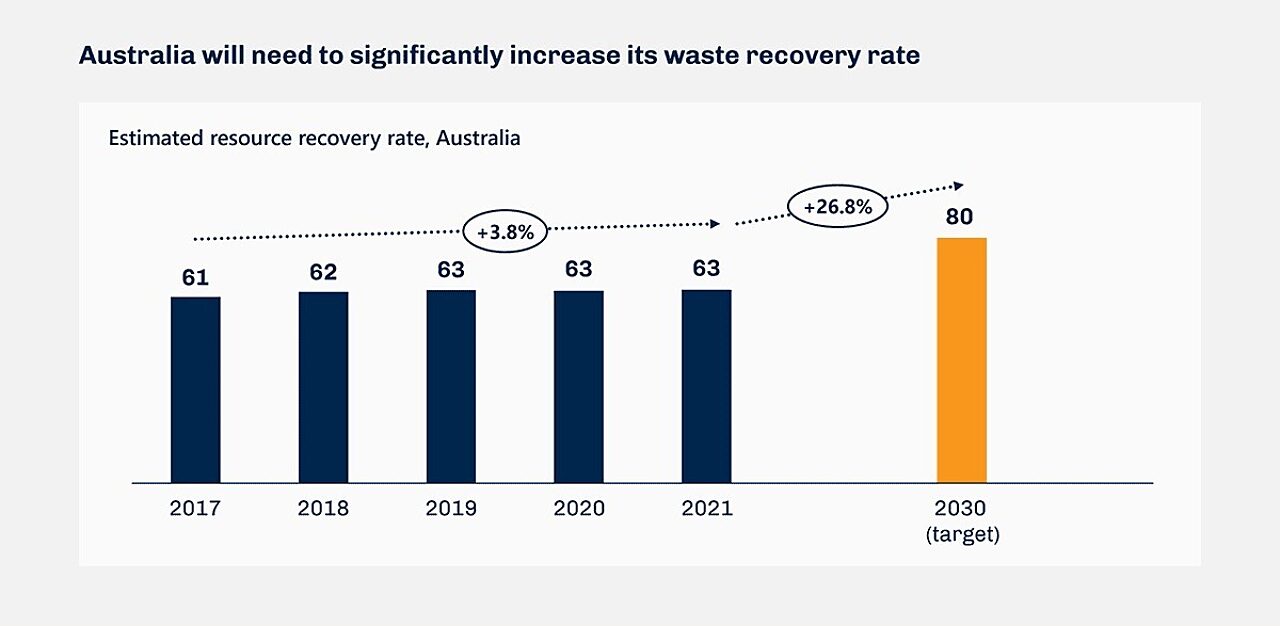

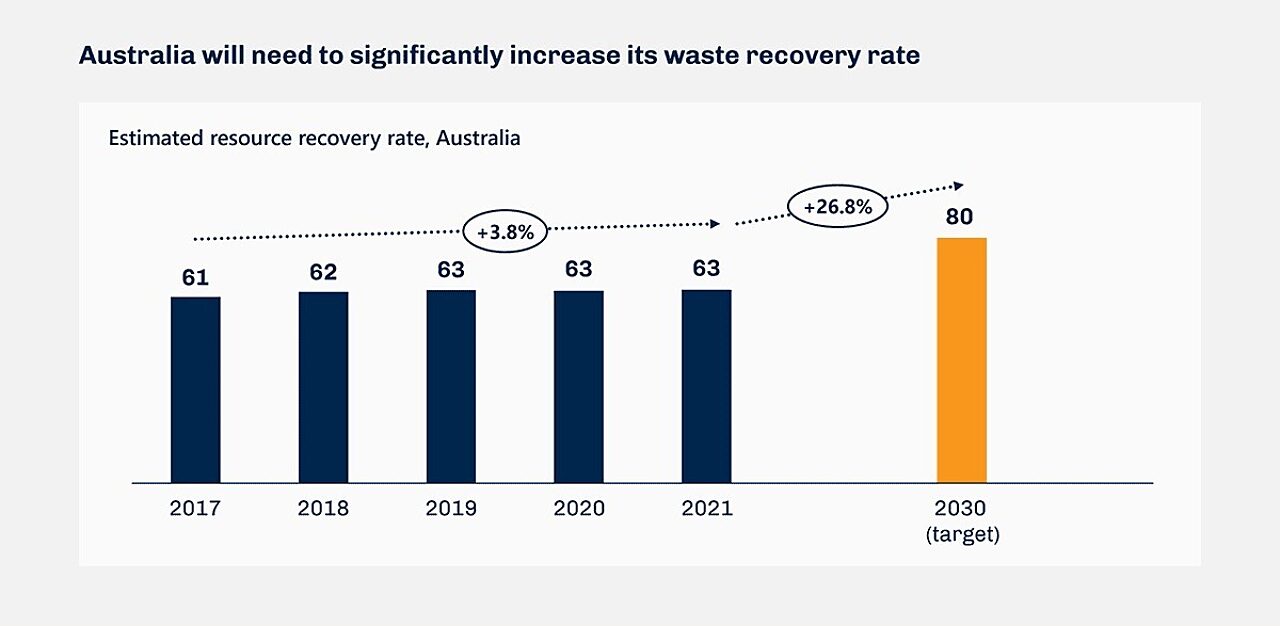

Australia’s National Waste Policy Action Plan aims to achieve an average 80 per cent resource recovery rate from all waste streams by 2030. This is a major step up from the 63 per cent average recovery rate achieved in 2021, a figure little changed over the previous five years. Getting there will not be easy, but it is important for Australia’s environment, economy, and international reputation.

No single policy lever will enable Australia to reach this goal in the stated timeline; it requires concerted effort, coordinated investment and a complementary suite of policy responses across all levels of government.

One important lever in governments’ policy toolkits is product stewardship schemes.

There have been recent successes for these schemes. For instance, as of November 2023, every mainland state and territory has a beverage container deposit scheme that rewards consumers with a 10 cent refund for every eligible container they return for recycling.

Despite the success of these container deposit schemes, product stewardship schemes more broadly remain underutilised in Australia, especially compared with other leading countries. These schemes are a particularly useful way for governments to get a head start on emerging waste streams, such as electric vehicle (EV) batteries and rooftop solar panels, which were both subject to record sales growth in Australia in 2023. (EV sales rocketed by 161 per cent in 2023.)

In this article, we draw on our experience working with governments on product stewardship schemes and broader recycling initiatives to explore the factors to consider in setting up these schemes.

Source: National Waste Report 2022

There is strong global momentum for product stewardship

At their simplest, product stewardship schemes oblige those involved in the design, manufacture, sale or use of products to reduce the environmental and human health impacts across the product’s lifecycle.

Product stewardship has become a recognised policy response to waste management in many countries. Pioneered in the European Union in the 1980s, product stewardship schemes have been adopted across the OECD, especially in the past 20 years. The number of schemes adopted globally increased by nearly 300 per cent between 2000 and 2015.

These schemes cover a broad range of products, notably small consumer electronic equipment, packaging, tyres, end-of-life vehicles and batteries. They are also being applied to emerging waste streams, such as EV batteries and solar panels.

Product stewardship schemes are useful where market forces and social conscience alone are insufficient to consistently drive industry behaviour to solve waste problems. They are especially effective when four conditions are met:

- Consistency – The material type and/or the construction of a product are relatively homogenous.

- Volume – There is a sufficient volume of a product or material supplied into the market each year.

- Value – The material contained in the product is useful as a recycled material (such as aluminium beverage containers) or otherwise its removal will reduce environment and/or human harm (such as end-of-life vehicle batteries).

- Improvement scope – Significant quantities of the end-of-life product or material are currently stored, stockpiled or disposed of in landfill, rather than recovered or recycled.

Successful product stewardship schemes abound. Norway’s deposit scheme for plastic bottles has achieved up to a 97 per cent recovery rate. Europe’s battery stewardship compliance scheme has led to a 6 per cent annual average increase in collection of waste batteries and accumulators, albeit from a relatively low base.

Australia’s intention to enhance product stewardship is yet to be realised

Progress has been slower in Australia.

In 2011, the Product Stewardship Act was established to achieve a simple and enduring national approach. It facilitated the establishment of mandatory and co-regulatory schemes, as well as accreditation of voluntary industry-led schemes. It aimed to cover more products and materials over time.

But it has not been as effective as it could be in changing industry behaviour, promoting better end-of-life product management, or significantly improving resource recovery rates.

A 2020 review of the Act found that many voluntary schemes struggle with set-up costs and free-rider issues. And a range of products – including solar panels, textiles, and end-of-life vehicle waste – have relatively low waste recovery rates. The review also found growing fragmentation across schemes, with 11 product groups that each have multiple schemes. While there may be good reason for this, there are clearly benefits in achieving greater harmonisation and consistency across schemes for similar product groups.

To date, Australia has opted for a voluntary approach for many schemes, which sets it apart from other developed countries, which tend to apply mandatory approaches. As of 2020, only eight of 40 schemes in Australia were regulated. The majority of these are regulated beverage Container Deposit Schemes. Since the 2020 Review, two additional legislated Container Deposit Schemes (Western Australia and Victoria) have commenced and joined the list of regulated schemes.

Governments should approach product stewardship from first principles

Product stewardship schemes need to be suited to their context. Different products, materials and industries need different kinds of schemes. For some, industry-led voluntary schemes will be appropriate. For others co-regulatory arrangements will be suitable, with government and industry working together. Some circumstances call for mandatory schemes.

To determine which product stewardship scheme design is most appropriate, governments need to ask a fundamental question: To what degree can market forces be relied on to sufficiently improve waste management and recycling outcomes across a product’s lifecycle?

Answering this question will likely reveal which (if any) of three key market failures are present:

- Coordination challenges. For large or decentralised industries with many participants, it can be difficult to coordinate participants to develop product stewardship schemes, even where there is appetite to improve waste management. It is easier to set up schemes in industries that are more concentrated and have fewer participants. Government involvement can help to overcome coordination challenges, particularly where there are many participants. Proxies for likely coordination challenges include the number of suppliers of a product or material, and the presence of internal mechanisms to solve coordination problems, such as an effective peak body or member-based association.

- Free-rider problems. Product stewardship can face challenges with uptake where producers or suppliers can gain competitive advantages from not participating in a scheme, or where they can obtain the benefits of a scheme without contributing to its costs. While some sectors have internal mechanisms to reduce free riding, this may require more substantial government involvement, for example through co-regulatory arrangements that establish a regulatory safety net to ensure that non-participants do not gain a competitive advantage. The size of implementation and operational costs are often good proxies for free-rider risks.

- Negative externalities. Some products can cause significant harm when they are not recycled or disposed of properly, there is a high volume of the product in circulation, or they are hazardous. While businesses sometimes have economic incentives to recycle or reuse these products, often these costs are not priced into businesses’ decisions. In such cases, product stewardship schemes can reduce negative externalities (such as littering or polluting the environment) by obliging industry to internalise product lifecycle costs and incentivise businesses across the supply chain to reduce the adverse impacts of their activities.

The incidence of these market failures should influence government’s role – whether it is encouragement and influence; offering information and support; providing monitoring and oversight; setting standards; or providing funding to support an outcome.

This process can be seen here.

It is time to act

With just six years until Australia is due to meet its 80 per cent target for resource recovery, the time to act is now.

Done right, product stewardship schemes can complement other resource recovery initiatives to support Australia’s transition to a circular economy. They also offer the opportunity to get on the front foot for emerging and fast-growing waste streams, enabling government to test and refine schemes while the level of waste generated is still relatively low.

Getting these schemes right is difficult. It requires strong technical understanding about waste management, economic and market drivers, the existing regulatory frameworks and the ability to engage and mobilise often fractured and polarised stakeholder environments to achieve sustained buy-in.

But governments cannot afford to get this wrong. Our citizens and communities are looking to government and industry to take the lead in securing a sustainable future.

Get in touch to explore how we can help you to design, establish or evaluate a product stewardship scheme or circular economy initiative.

Connect with Sam Abusah on LinkedIn.

Prepared with input from Lauren Ware and Kate Grutzner.