Idea In Brief

Meeting diverse needs

Intersectional analysis is vital for any policy and program designer who is aiming to meet the diverse needs in a population. Intersectional analysis can provide policymakers with a better understanding of the compounding challenges experienced by individuals in order to facilitate better-tailored policies that begin to address systemic and structural problems.

Analysis in action

In our work with Ontario's Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services to evaluate a program to combat sex trafficking, we found that efforts could be most effective by considering the needs of groups at highest risk. Working with a local government in Australia, we aimed to find ways to consider intersectional impacts across a spectrum of needs.

Five steps to take

Policymakers should consider five steps to more inclusive and equitable policies: build understanding and trust to aid data collection; collective disaggregated data with an intersectional lens; look at intersecting and cross-issues; listen to diverse voices of people potentially impacted; and create opportunities for cross-community collaboration.

COVID-19 has shone a spotlight on longstanding drivers of health inequities, including adverse working conditions, access to housing, childcare and economic disparities.

These important determinants of health are interlinked with class, ethnicity, gender identity, education level and other factors in a complex and cumulative way, making these inequities impossible to ignore.

The cumulative impact of social determinants can also be seen in social issues such as human trafficking, where class, Indigenous identity, ethnicity, gender identity, age, and experience with child protection each contribute to the risk of being trafficked.

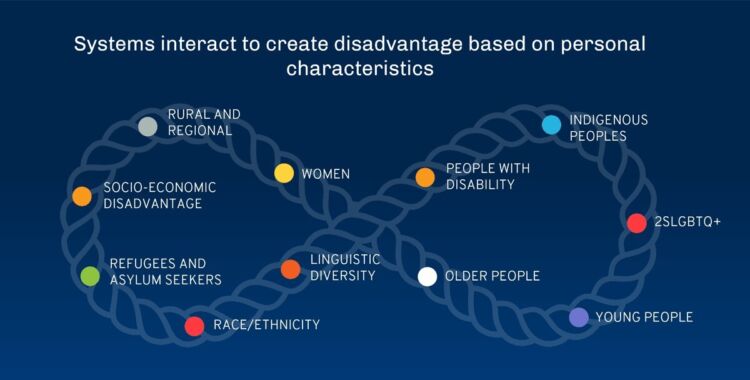

Intersectional analysis considers what occurs when multiple axes of gender, ethnicity, class and age combine. This perspective can illuminate how structures of inequality are crosscutting and mutually reinforcing. These structures may be interrelated but are different systems of inequality.

It is clear that public services do not always deliver equitable outcomes:

- In Canada, the Ontario Human Rights Commission observed disproportionately high incidences of Indigenous and Black children were taken into care in the child welfare sector.

- The poorest people in the UK are 2.5 times more likely to have diabetes at any age than the average person.

- The health status of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples is poor compared to the rest of the Australian population. For example, there is an estimated eight-year gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous life expectancy.

Policymakers increasingly believe a big step towards ending systemic inequality can be taken through more widespread use of disaggregated data – that is, data that can distinguish between gender identity, race, ethnicity and more.

Collecting and analysing disaggregated data allows organisations to look at how policies and programs impact individual groups. But importantly, it also allows us to look at how these factors intersect and can have a multiplying effect.

Intersectional analysis is vital for any policy and program designer who is aiming to meet the diverse needs in a population. In this article we explain how intersectional analysis can provide policymakers with a better understanding of the breadth and complexity of compounding challenges experienced by individuals in order to facilitate better-tailored policies that begin to address systemic and structural problems.

COVID-19’s divergent impacts show the power of intersectional analysis

As policy makers and armchair commentators around the world have reviewed the pandemic, a few things have leapt out. The impact of lockdowns and work from home directives hit very differently for middle-class people in white-collar jobs versus those in frontline essential roles. Add in a few additional socio-economic factors like single parenting, housing instability or pre-existing health conditions and you have a maelstrom of intersectional factors that mean people’s pandemic stories have been very different.

We know hindsight is 20:20. The challenge for policymakers now is to consider and manage how intersectional factors will influence not just the ongoing COVID recovery, but all other policy decisions.

Policies need to tailor their solutions to the unique needs of different parts of the population.

Intersectional analysis supports the development of more effective policy and programs

Nous recently worked with Ontario’s Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services to evaluate a prototype program that brings police, child protection workers and two Indigenous agencies together to identify and locate children and youth who are at high risk of being sex trafficked and have absconded.

These three agencies pool their resources and share information to locate the child and/or youth and offer them supports, including a safe place to stay, to prevent further exploitation.

Public Safety Canada[5] found the children and youth with higher risk of being sex trafficked include:

- Indigenous girls

- new immigrants

- children in care

- people living with disabilities

- 2SLGBTQ+ people

- people struggling socially and/or financially.

Each risk factor has a multiplying impact. Like the COVID example, each socio-economic feature points to different systems of discrimination and/or marginalisation that are cross-cutting and mutually enforcing.

In evaluating the anti-human trafficking program, we gathered input from people with lived experience and from Indigenous agencies to inform the recommendations. We identified that the Indigenous organisations took a wholistic approach to managing children and youth who are at risk of being sex trafficked. This meant that as soon as a child was identified as at risk of being trafficked, the organisations identified supports to address the physical, emotional, mental and spiritual needs of the individual.

We recommended that the Ministry look to this approach as a best practice for addressing the needs of children and youth who are being trafficked. It looked at each child in totality and did not focus on only their Indigeneity but sought to address their family situation, their historic trauma and any other identity that they might bring to the table.

Intersectionality means addressing the needs of the whole person. This requires an individualised response. Ontario’s efforts to combat sex trafficking will be greatly improved if they can address each person’s intersectional needs.

Each person has unique needs

The use of intersectional analysis is also an increasing area of focus for local government authorities. Nous has partnered with local government authorities in Victoria, Australia, to explore the needs of different vulnerable cohorts that experience intersectionality, with the aim of determining how to more effectively engage and service the needs of those cohorts.

In our work with one local government, we reviewed the government’s publicly available data with an intersectional approach and undertook direct user research with vulnerable cohorts, service providers and government staff supporting those cohorts.

Our findings, while at times common across the cohorts, also varied greatly. Use of our spectrum of needs framework was a helpful mechanism for articulating the findings and for the structured development of place-based recommendations for each cohort.

Five things policymakers can do

The need to address the underlying systemic and structural issues that drive inequities is now possible with data analytical tools that can easily analyse disaggregated information.

As policymakers support communities where there are differential impacts, disaggregated data can guide decisions around where and how to deploy resources. Those policymakers who default to a one-size-fits-all approach will likely find that the outcomes fail to address the underlying issues and may have unintended consequences.

Policymakers with the courage and creativity to grapple with questions of intersectionality can design programs that will have a lasting impact on whole populations.

These five steps can help to build more inclusive and equitable policies:

- Build understanding and trust to aid data collection. Communicate your intentions behind the data collection to encourage respondents to volunteer their personal information and mitigate sensitivities to data collection from various groups (such as Indigenous, racialised, 2SLGBTQ+).

- Collect disaggregated data with an intersectional lens. The data allows policymakers to see who, how and where inequities are playing out and to provide a sense of where targeted policies will have the most impact.

- Look at intersecting and cross-issues. Be open to thinking creatively and considering unintended consequences of policy decisions. Incorporating a truly intersectional approach requires routinely considering how various cohorts may be impacted, how structural factors connect with each other, and whether one approach to address one policy challenge may undermine efforts of those working on a different but intersecting issue. In analysing data, include ‘interaction terms’ in statistical models to understand how outcomes vary at the intersection of two or more categories (for example, gay black men).

- Listen to diverse voices of people potentially impacted. The data alone will not tell the whole story and some cohorts may not show up in the data. Valuing voices means promoting the storytelling of those most affected by policies and practices. Listening to a range of cohorts (including Indigenous, racialised, 2SLGBTQ+, women, and people with disability) and listening to divergent voices within and between cohorts will expose different experiences, each of which can lead to different solutions. Centring their substantive suggestions and values into policy and programs will have a greater impact.

- Create opportunities for cross-community collaboration. Creating tables where diverse perspectives can come together to consider how issues connect with each other, and whether one approach will undermine efforts on a different but intersecting issue, may lead to innovative findings and policy recommendations.

These steps are not always easy, but they are achievable with organisational goodwill coupled with expertise from those who have gone on the journey before. Governments that decline to take action will be failing their citizens.

Get in touch to explore how we can support you to take an intersectional approach to policy design and program evaluation.

Connect with Abby Nduva on LinkedIn.

Co-authored by Susan Underhill during her time as a Director at Nous.

Prepared with input from Angela Chen, Antonia Instone and David Diviny.