Idea In Brief

Strong ecosystems balance focus and adaptability

They build clear areas of competitive strength while staying agile enough to adjust direction when conditions, stakeholders or opportunities shift.

Failure is essential for innovation quality

High‑performing ecosystems embrace constructive failure to learn quickly, avoid propping up weak ideas, and redirect resources toward stronger opportunities.

Ecosystem design must align technology with real needs

Successful ecosystems match research‑driven innovation with market demand so ideas have viable pathways to scale and real‑world impact.

Innovation ecosystems are critical to tackling our most pressing social and economic challenges. In a world of accelerating technological change, no organisation can innovate alone. Governments and universities – key stewards of these ecosystems – face growing pressure to deliver more impact with the resources they have.

But what does ‘good’ really look like?

At Nous Group, we have worked with leading university-based and government-led innovation ecosystems worldwide. Here are five success traits we have seen that consistently set high-performing ecosystems apart.

1. Balancing adaptability with ‘doubling down’ for competitive edge

There is tension between being nimble and notable.

Innovation is uncertain. Success is not guaranteed and our future societal needs are hard to predict. Ecosystems therefore need to spread their bets so that they are well-placed (and not closed off) when the world changes. But doing everything is not a viable strategy either. External stakeholders often expect ecosystems to align themselves with national priorities, and build vertical integration so they add compounding value to ideas at each stage of the innovation pipeline. Getting this balance right is a major challenge.

Have bold ideas, loosely held.

Good innovation ecosystems have a reputation in something. They make a point of letting others know this is what they do best. This creates expertise and momentum by encouraging talent and capital to cluster in a few key areas (referred to as ‘agglomeration effects’). The best ecosystems create this type of competitive edge and at the same time plan to adapt. Adaptability might look like short strategic cycles to reprioritise effort, governance mechanisms to scan for external trends, and open funnel designs to accommodate good ideas wherever they arise.

Case Study: KAUST has a clear competitive edge whilst remaining responsive

King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) is Saudi Arabia’s flagship STEM research university. The innovation ecosystem that it manages began as the Kingdom’s first mover – launching the first accelerator and first women-founder bootcamp. However, the regional innovation landscape is maturing rapidly. As it does, KAUST is evolving from filling gaps to staking its reputation in key areas aligned with its comparative advantage in deep-tech research and unique positioning on the Red Sea. Yet agility remains. KAUST’s network and decision-making mean it can still rapidly stand-up programs in response to sudden demands. This balance – clear focus with adaptive capacity – keeps KAUST competitive and relevant.

“At KAUST we love working with our partners to understand their challenges and design solutions,” says Haitham Alhumsi, KAUST’s Director of Innovation Ecosystem Development. “At the same time, if you jump at every opportunity then spread your resources too thin and dilute your impact. You have to love the impact more than you love the problem, and let your passion for impact guide you on where to focus your attention.”

2. Fuelling success by enabling failure

Failure is uncomfortable but inevitable in innovation ecosystems.

Failure is just as important to innovation ecosystems as creativity. In fact, ecosystems that fail well create more space for creativity. This is because complex problems rarely yield to perfect plans: they demand trial and error. Failure helps us learn what works, discard what doesn’t, and iterate towards more viable solutions. But encouraging failure can feel risky due to performance targets, sunk cost fallacies, or important ‘pet’ projects, and so the default strategy of keeping weak ideas alive (with generous grants or low rents) ends up being counterproductive at a system-wide level.

Embrace and promote failure.

High performing ecosystems cultivate a “healthy” failure rate. In the markets where we operate, startup failure rates are typically around 40 to 60 per cent in the first five years. Managed innovation ecosystems with failure rates considerably lower than this might be over-cushioning founders. The sweet spot is solving market failures (de-risking good ideas) without distorting market signals (propping up bad ideas). This might look like carefully designed stage gating to ensure that innovative ideas and founders are demonstrating their continued value along the journey, but it is also about creating a culture where the tough decisions are made, which will often mean letting things go.

Case Study: Alberta Innovates introduces constructive challenge through dedicated advisors

Alberta Innovates is Canada’s largest provincial innovation agency. The ecosystem has Technology Development Advisors (TDAs) that mentor founders through the innovation journey. They act as a form of stage gating by offering guidance but also challenge, forcing tough decisions when ideas stall. By encouraging pivots and even abandonment, TDAs prevent “zombie projects” and free up ecosystem resources for stronger bets. This culture of constructive failure helps the ecosystem learn fast and scale what works.

3. Designing for both technology push and market pull

Innovation fails when it does not meet a real need in the market.

University-based innovation ecosystems often excel at developing new technologies in their labs and libraries. There were thousands of patents granted to UK universities last year alone which demonstrates there is no shortage of innovation supply. But many revolutionary ideas struggle to reach the market – and disappear in the ‘valley of death’ – because the demand side of the equation is not clearly understood.

Ask: Technology ready for whom?

The best innovation ecosystems avoid this trap by designing for two forces: technology push (ideas driven by research) and market pull (demand from customers). The successful innovation ecosystems we work with incentivise researchers and entrepreneurs to both invent and to listen to what the market needs. The mindset shift therefore moves away from traditional technology readiness levels (TRLs) and towards a form of commercial readiness assessment instead.

Case Study: Unit M at the University of Manchester aligns research to industry needs

Unit M, the University of Manchester’s innovation unit, operates with a mandate to accelerate inclusive growth. As the University’s gateway for innovation it partners with startups, scale ups, academics, policy, and industry. Since its inception, it has embedded market pull into its model, ensuring innovation responds to real-world challenges. Offering a single entry point to the University’s talent, ideas and resources, Unit M drives collaboration and innovation. Its structure integrates innovation partnerships with industry – including with Bupa – alongside user-centred design expertise, to ensure innovation solves real problems, for real people and real businesses.

4. Addressing the most important bottleneck first

“We can always do better, but we can’t do everything.”

Innovation ecosystems are dependent on a constant flow of research, ideas, talent, and capital. These are the basic components of innovation. The people that manage these ecosystems generally have a long list of things they would like to improve the efficiency (input to output conversion) and effectiveness (quality of outputs) of the innovation pipeline. But there is nothing strategic about a list. Ask around enough and you will typically find one of these basic components is a bottleneck for the system overall: “research quality is not where it needs to be,” “we just can’t get the right founders in seats,” or “VC is not willing to put money on the table”.

Address the biggest bottleneck first.

Performance improvement initiatives that are geared towards an ecosystems critical bottleneck are likely to have the greatest impact. Ecosystem must coordinate all levels at their disposal to do this. Importantly, we see the bottleneck for ecosystems can change significantly depending on operating context. For mature ecosystems in Europe, it might be attracting capital whilst for well-funded infant ecosystems in MENA for example it might be getting savvy business leaders to run startups.

Case Study: Hub71 unlocks new capital pathways through risk-sharing structures

As Abu Dhabi’s global tech ecosystem, Hub71 identified an opportunity to strengthen early-stage funding by addressing investor hesitancy around high-risk, early-stage deals. In response, Hub71 introduced the Angel Investor Support Package, which incentivises the formation of angel syndicates by covering setup and legal costs for investments into Hub71 startups. This targeted approach, combined with streamlined licensing and regulatory facilitation, has catalysed new capital flows and enabled the formation of active angel groups such as Qora71. Within five months, Qora71 mobilised over 130 investors and deployed more than USD 2 million in startup capital. Its subsequent acquisition by Stryde, a DFSA-regulated digital investment platform, led to the creation of Stryde71, a dedicated vertical focused on venture capital syndication. This demonstrates how targeted incentives can activate capital, deepen investor engagement, and strengthen the foundations of technology ecosystems.

5. Brokering well between ecosystem participants

The challenge of building connections and facilitating creative collisions.

Innovation can sometimes seem like alchemy because it is a by-product of countless collisions of ideas and people. Ecosystems need collaboration across the ‘triple helix’ of partners (industry, higher education and government) and between founders that make new and novel connections. No single actor can drive innovation on its own. In disconnected ecosystems, experiments are run top-down in isolation. In connected ecosystems, connections occur organically, via participants themselves.

Do not leave spontaneity to chance.

High performing ecosystems create the necessary conditions for innovative connections to happen. This is what is commonly referred to as “engineered serendipity”. Often this involves researcher and industry ‘mixers’, formal R&D partnerships, or networking events. But more subtle design choices like the use of space and shared workspaces can encourage entrepreneurs to regularly brush shoulders, exchanging ideas.

Case Study: Edinburgh’s purposeful design creates opportunities for cross-sectoral collaboration

The Data-Driven Innovation (DDI) initiative from the University of Edinburgh demonstrates how thoughtful design choices can make collaboration stick. Its six innovation hubs co-locate industry, academia, and government in a shared space where ecosystem participants can work in structured ways alongside each other and have informal “water-cooler” exchanges that spark ideas. Aligning the interests of different actors is also key. As DDI Head of Strategy, Gemma Cassells and DDI Head of Delivery John Scott note “collaboration isn’t left to chance. We’ve deliberately designed the system, the spaces and the incentives so partnerships are sustained, not just transactional.” One key DDI project, Smart Data Foundry demonstrates this because it turned regulatory and policy goals – like tackling financial exclusion – into a business opportunity. Specifically, NatWest shared anonymized transaction data to meet social impact commitments while gaining insights that improved its own services.

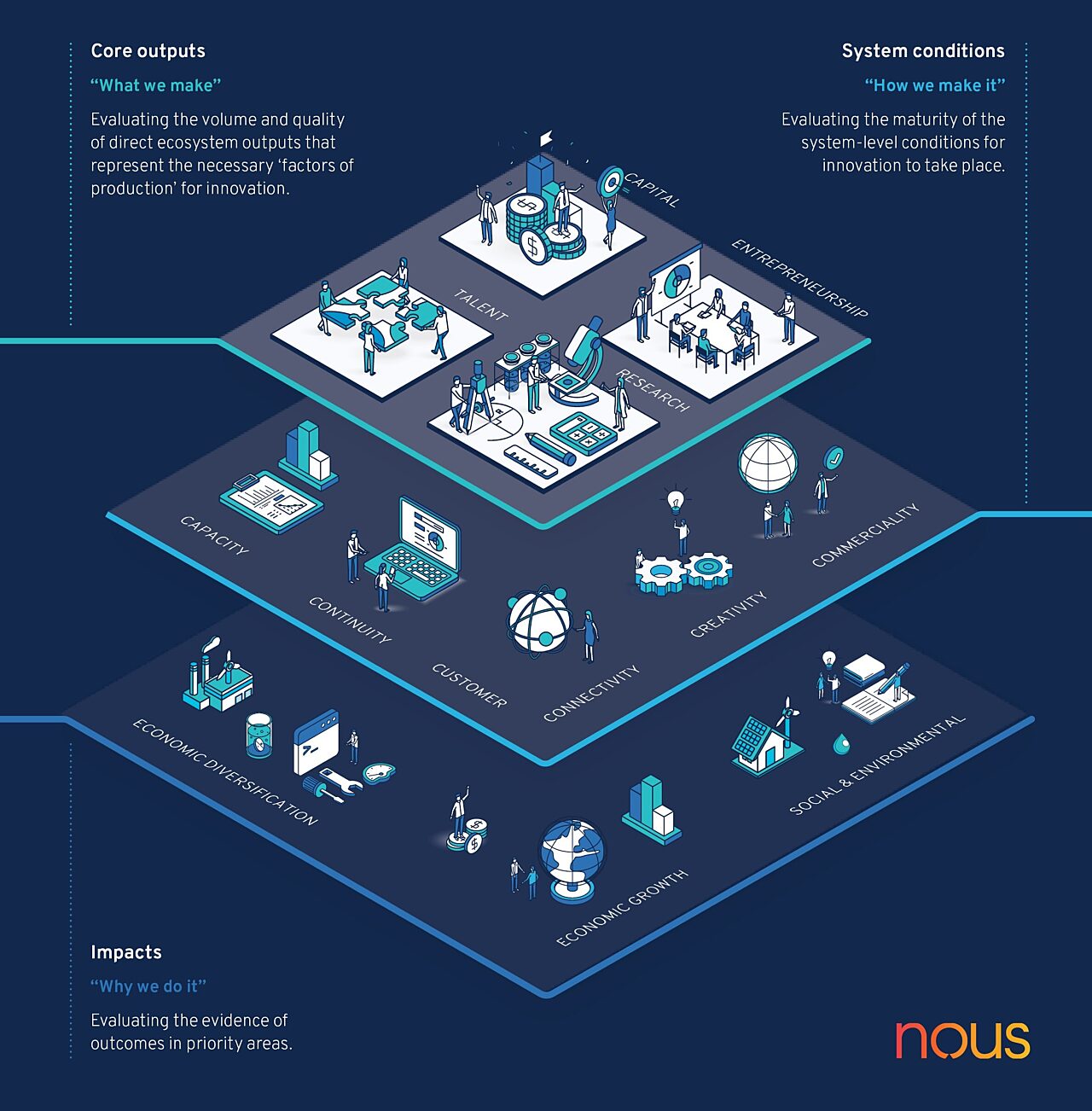

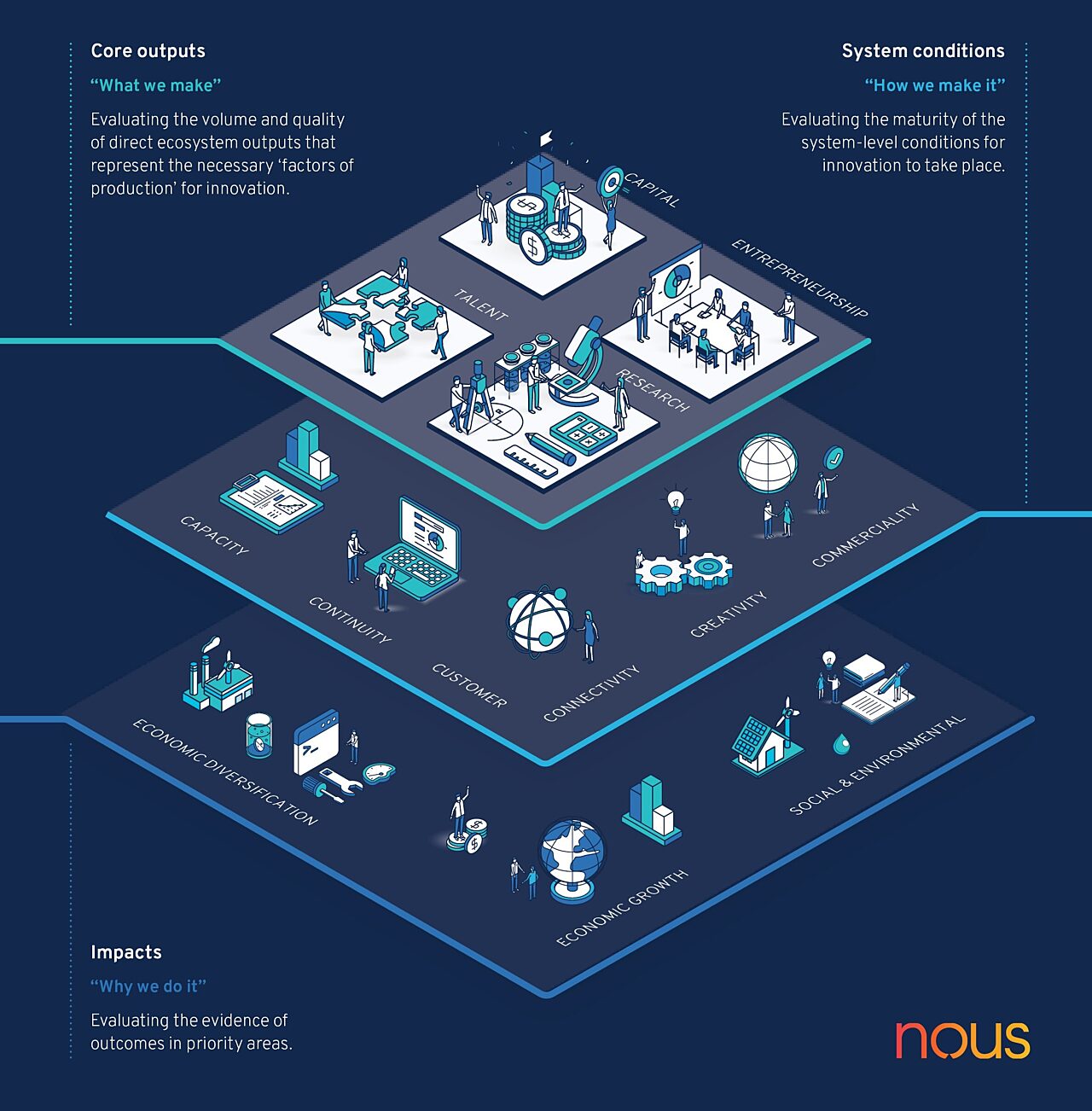

Our three-layer impact framework helps ecosystems to assess their health and maturity

Innovation is complex, non-linear, and unpredictable. It’s hard to gauge how an ecosystem is tracking, and where it is exhibiting these five traits or where it’s lagging behind.

At Nous Group we’ve developed an integrated framework for assessing ecosystem health and maturity. This framework looks at three layers: what we make (the core outputs), how we make it (the system conditions) and why we do it (the macro impacts).

In an age of increasing expectations and fiscal constraint, stewarding successful ecosystems has never been more challenging, or more important. These five examples show what’s possible.

Get in touch to discuss how you can turn your higher education institution into an innovative, world-class sector leader.

Contact James Rendoth and Laurie Martin on LinkedIn.